Government behind us

“Most people cannot easily give up power. Most people cannot peacefully accept that others with whom they disagree should have power over them. Most people cannot resist the temptation to enrich themselves through political office rather than work to improve the community as a whole. The historical record often shows these sad realities.” – Brian A. Pavlac[1]

We should look behind us briefly before heading over the next hill and discussing the future of government. In this post, I’ll talk about past governments, from oldest to newest and coincidentally generally worst to best, using the six attributes I discussed in my last post. Via this history, a pattern emerges showing how increases in representation have lead to prosperity, and subsequent reductions in representation have lead to decline.

Monarchy: All For One

Monarchy is often cited as the most common form of government throughout history, especially before the 1800s, because it’s both simple at its core and the most attractive position for an individual. “Do as I say” is much simpler than a constitutional agreement. Also, the hereditary nature of so many monarchies and dictatorships is a natural extension of familial kinship and the human desire to help your offspring succeed. And as for attractiveness, if you were confident you could secure your safety, I suggest that most people would be attracted to absolute power. And for people that think they wouldn’t want that, imagine being able to choose your favorite leaders to run things for you for as long or short as you wanted them to.

In other words, its good to be king.

These things combine to make autocracy in general the most common government (tho that seems likely to change in the future). Ambitious individuals tend to continue concentrating power to themselves their whole lives if they can. And before there was millennia of history to draw from, few powerful people have had the motivation to put serious work into devising new forms of government. It simply took time for us to have both the knowledge wrought of thousands of governments and the random chance to find powerful individuals the motivation to change the structure of their people’s government.

Autocracy has the fewest leaders, the least representation, no separation of powers, and very rarely has any limitations. Coupling of sub-governments has been anywhere from weak to strong depending largely on the size of the nation. Policies often drastically change between leaders and are generally unfair and inconsistently applied to the general population. Autocracies also have the least focus as to what actions they take, and thus changes in autocrat can have drastic consequences.

I’d have to say, and I think most people would agree, that autocracy is the absolute worst type of government. The concentration of power into one person leads to short-lived leaders, catastrophic decisions, and inconsistent policy. Because there is no representation of the people, most of the kingdom’s subjects are treated unfairly and the nation’s economy almost always badly stagnates, even if a short period (couple decades) of growth happens. And when a good and careful ruler has a long and successful reign, the next king is likely to ruin it all over again.

Oligarchy: Minority Rule

In reality, a monarchy is a type of oligarchy, since the family of the monarch is the controlling group with their own traditions of how power is passed to their various members. Any autocrat needs supporters. These supporters may be chosen for various official positions, including eventually the position of autocrat itself.

The concept of oligarchy is tricky because so many governments can be considered oligarchies by one definition or another. But there is simply no other way to characterize the governance of places like India under the rule of the British East India Company, or China under the rule of the Communist Party. In these situations, even if a single leader is chosen, no single ruler determines the fate of the nation. Rather, the fate of such a nation is determined by the organizational politics of the organization in power.

Oligarchies tend to invent stories about why the ruling elites are the rightful rulers. Stories like the divine right of kings or the supposed meritocracy in ancient and modern China, help the elites convince the masses that they’re the rightful rulers. More recently, oligarchs have manipulated democratic-style systems in attempts to convince their population they were chosen by the people. As I said in my second post, these stories are simply one of many techniques used to keep power, and don’t help understand the government itself.

The iron law of oligarchy states that rule by an oligarchy is inevitable in any organization, democratic or otherwise. It can certainly seems to be the case that all countries have some level of oligarchy at a hidden but usuall not-so-hidden level. But what I’m talking about here is an oligarchy of a very limited few. This kind of oligarchy is a step in the right direction away from pure autocracy. Oligarchies have more leaders (by definition), usually slightly broader representation, and also sometimes have some limitations and separations of power. As more people are given official power, structure and limitations are sometimes created so the oligarchs can have reasonable expectations of their peers. Oligarchies with few limitations often devolve into autocracies because of a vicious cycle that leads rule by a few to consolidate power to even fewer over time.

While representation can be broader than in an autocracy, by definition representation is still narrow in an oligarchy. This makes them unfair to the people at large, and so the derogatory use of ‘oligarchy’ is entirely justified.

That said, some oligarchies are better than others.

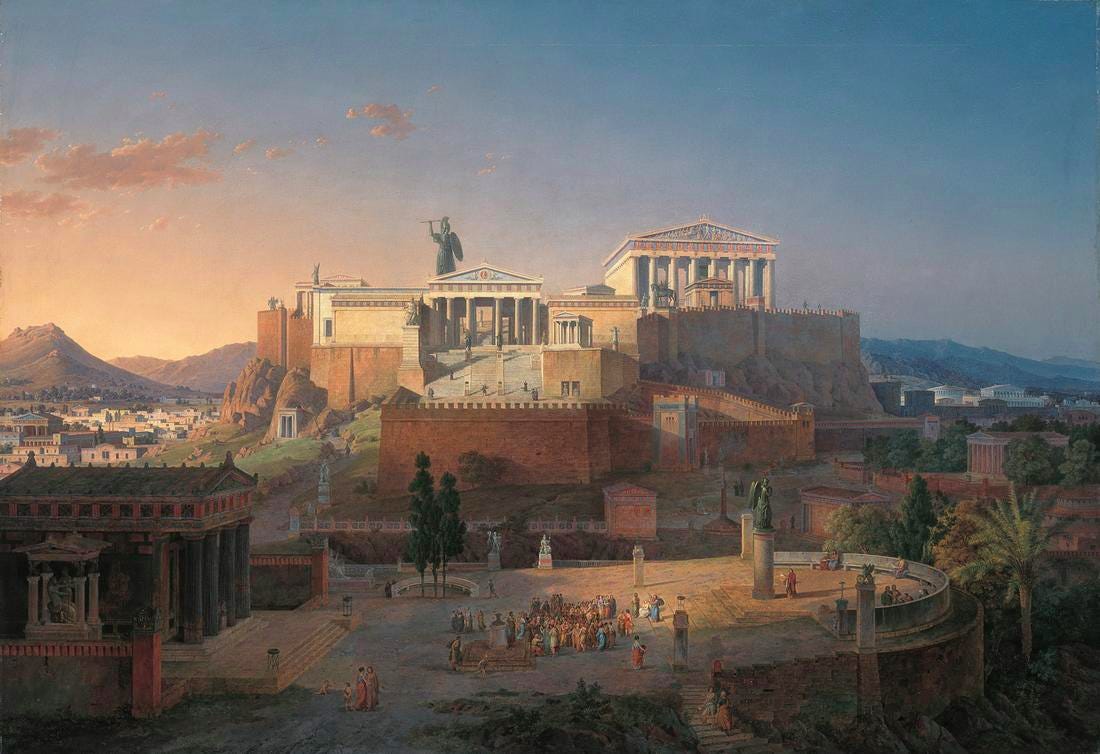

Rise of Representation in Greece

Things start to get interesting whenever a society significantly increases representation.

After a period of unrest, proto-democratic institutions were created, likely in the 700s BC[8]. The Spartan Apella, which voted on the powerful Ephors and other magistrates, consisted of perhaps 3% of the population[1] at the height of the Spartan empire. It’s unclear to me whether this percentage may have been greater before Sparta accumulated massive numbers of slave-like helots that eventually made up about 80% of the population[2]. Despite potentially being naked, they voted by shouting, choosing the loudest collective shout to determine the outcome, which could be seen as a primitive form of range voting.

A man once argued that Ancient Sparta (circa 850 BC) should set up a democracy, and the famous lawmaker Lykurgus, credited with establishing institutions that lead to Sparta’s rise to power, replied:

“Begin with your own family“

Sparta was still an oligarchy, but one with some limited democratic structures. Separation of powers was likely minimal, as was limitation of what the government could do. But this was almost definitely a huge increase in representation at the time, and because of this, Sparta built the wealth necessary to sustain a major army and building an empire.

The Apella was soon undermined in the 600s BC when Theopompus and Polydorus created a provision allowing kings and the Gerousia to nullify any “crooked” decision of the citizens.[5] The Spartan empire eventually suffered irrecoverable losses in the 370s BC and few traces of it remain today.

Meanwhile during the late 600s BC, harsh and legendarily draconian rule by the archon Draco oppressed the population of ancient Athens. Again after a period of unrest and feuds among the aristocracy in the 590s BC, the archon Solon reformed the Athenian oligarchy by establishing the democratic Ecclesia and democratized the Boule so it consisted of citizens chosen by random drawing. Between 10-20% of the people were citizens entitled to vote in the Ecclesia[3], which decided issues the Boule brought up to it by plurality voting. Archons were also elected by the Boule, tho only elites were eligible. The Areopagus, a council of ex-archons, still retained judicial power and other supervisory powers.[4] In 561 BC Peisistratos overthrew the Athenian government and controlled the democratic institutions by coercion rather than abolishing them altogether[6]. But these institutions were revived after his son was overthrown in 510 BC by a coalition lead by Cleisthenes, who even expanded the representation of Athens’ citizenship. In the 460s BC, Ephialtes enacted a third set of reforms removing the supervisory powers of the Areopagus and opening the office up to all citizens.

The Athenian government was by far and away more representative than the Spartan government. There were probably a few more leaders, given that they had more high councils, and there was even some limited separation of powers. The government was still all powerful tho and the Athenian government was still controlled by elites who often maintained influence via corruption.[19] The government was also criticized as “mob rule” as they often did poorly in wars started by popular vote.

The Athenian constitution was also unstable for most of its existence, since it only required a majority vote to change it until the decades immediately after 400 BC. After that time, a trial in the Legislative Court was required to revise or repeal permanent laws (vs temporary “decrees”).[21] In this way, late-state Athens had a higher-than-majority level of agreement needed to change existing laws, including the constitution. There was still no conception of a difference between constitutional law and normal law, as Aristotle would be the first to write about such a formal distinction later in the 300s BC. However, they still had the much weaker majority level of agreement required to make new laws.

These democratic institutions survived with minor hiccups (devolutions into autocracy) until Phillip II of Macedonia defeated Athens in 338 BC. Athens remained relatively wealthy for centuries, but never regained its democratic institutions nor a place of major influence until the modern day. Athens was one of many Greek cities that had democratic institutions like the Ecclesia. Without a doubt, the massive increases in the people’s representation in government were critical to establishing the most successful civilization in the western world up to that time, not only in Athens but in the entire Greek peninsula.

Both the Spartan and Athenian cities had somewhat inclusive institutions rise out of periods of turmoil, became wealthy, and then engaged in empire building. The institutions that worked well for domestic policy in these cities didn’t work well for an empire, and the constant warring with their neighbors certainly didn’t help stabilize their societies. Because Sparta and Athens were not very open to peaceful diplomacy, eventually larger enemies were able to defeat both cities.

The Roman Republic

Before the Roman Republic was created, the Roman Kingdom was already a constitutional monarchy with some small but significant representation of the elites known as patricians. A body of patricians called the senate provided some checks on the power of the king, as well as having the power to elect new kings. Roman citizens were even ostensibly given the power to accept or reject a new king by vote. Still, the patricians were the only class allowed to hold government office, and thus Rome was still an official oligarchy.

The Roman Republic was established in 509 BC after resentment of Etruscan rule escalated and the patricians overthrow the Etruscan king Lucious Tarquinius Superbus. The king was replaced with two consuls that ruled jointly with limited terms elected by the citizens, tho still only patricians could be elected as consuls and the senate determined nominees for consul[7]. The proportion of citizens in the Roman Republic was about 20-25%[14][15], and probably a larger proportion in the early republic. This oligarchical period of the Roman Republic is called the Era of patricians because the patricians still held almost all of the power.

In 494 BC, things dramatically changed when a large group of plebeian soldiers seceded to Aventine Hill demanding representation. Subsequently, the plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were created, both elected by the body of Roman citizens. The plebeian tribunes had the power to create law binding the plebeians, veto actions of the Roman senate, and judge the lawfulness of a magistrate’s actions. Eventually, the tribunes’ powers were expanded so laws were binding to all people (except perhaps magistrates). The plebeian aediles began as a minor role, but around 446 BC they were given the authority to record senatorial decrees, since Roman consuls tended to sneakily modify decrees in transcription. The power of plebeian aediles grew over time to rival the power of consuls.

In 445 BC, the plebeians demanded that the office of consul be opened to allow plebeians to be elected. In 443 BC, the magistrate office of censor was created – a move by the patricians to regain exclusive control of the highest office, as censors were elected exclusively by the patrician class. And in 366 BC, the magistrate offices of praetor and curule aediles were created which allowed plebeians to hold executive office, albeit subject to veto of the offices of Dictator, Censor, and Consul.

In time, senators and tribunes engaged in substantial quid pro quo, tying their motivations together. By 312 BC, a significant number of magistrate offices were held by plebeians, but it became more and more difficult for citizens to be elected unless they were from an established political family. A new class of plebeian aristocracy was being created that would eventually rise up to the same level as the patricians and merge with them.

By 287 BC, the average plebeian was poor, but the senate refused to provide the relief they wanted. The plebeians again seceded, this time to Janiculum Hill, demanding that their needs be met. The plebeian elite used this opportunity to remove the last blockade from the tribunes, passing the Hortensian Law that allowed tribunes to consider and create law without the approval of the senate. Despite this win for the plebeians as a legal class and others legal victories later that century, the plight of the average plebeian did not improve over the next 150 years and beyond. Wars, including civil wars, were fought continuously and the economy continued its decline.

Throughout the Roman Republic, an officer known as the Dictator could be appointed by the senate for a period of 6 months, and like the modern meaning, had absolute and unchecked power over the republic. Whenever a Dictator was appointed, the old monarchy was effectively temporarily reinstated for a period lasting 6 months. Between 501 BC and 202 BC, there was an average of 1 Dictator appointed every 3.75 years.[20] After 202 BC, the position of Dictator went defunct for 150 years.

It can be argued that Rome became an Empire during the First Punic War around 250 BC, and that the creation of an empire lead to economic disparity and powerful generals that undermined the institutions of the republic. As soldier citizens began going on longer campaigns, many of them were unable to tend their farms and were unable to compete with vast farmsteads worked by slaves. This forced many to sell their farms, decimating the middle class. This is the first video in a series that goes into this in more depth:

Between 133 and 49 BC, serious economic issues lead to an intensification of class struggle where poor plebeians tried unsuccessfully to use government to alleviate their poverty through the use of government action. For example, after a succession of unprecedented and tradition-breaking legal moves by the senate against the tribune Tiberius Gracchus and vice versa, Tiberius’s pet law that would limit the amount of land an individual could own was passed. Soon thereafter his attempt to become the first Tribute to serve two terms turned violent as a number of senators murdered Tiberius and 300 of his supporters in the street during the vote.

The period continued in volatility where both the powers of the senate and the republican institutions were eroded further. Political corruption and violence was widespread. Provinces were run under absolute rule by their governors. The cost of political campaigns skyrocketed fueled by the enormous personal wealth politicians could amass by abusing their authority. Politics were increasingly polarized between the elites and the people, and continuous war was waged.[9]

“Our age, however, inherited the Republic as if it were some beautiful painting of bygone ages, its colors already fading through great antiquity; and not only has our time neglected to freshen the colors of the picture, but we have failed to preserve its forms and outlines.” – Cicero circa the 1st century BC

By broad qualification, the Roman Republic was similar to the Athenian government. The number of leaders was likely slightly higher, there was slightly more separation of powers, and while the percent of the population that could vote was slightly higher, it seems the aristocracy had more power in Rome than in Athens. So the representation was rather on par if not slightly less representative in the Roman Republic than in Athens, and was certainly less representative near the end of the Republic. And the government had almost absolute power with very few if any limitations. Ancient Rome had above majority thresholds required to pass laws, in the form of various veto powers in what could be seen as a multicameral system. But its constitution was, like Athens’, constantly in flux because no distinction was made between constitutional law and normal law, and thus the level of agreement needed for structural change was small by modern standards.

“Veni, vidi, vici.” (I came, I saw, I kicked its ass) – Julius Caesar

The end of the Roman Republic was clear when Julius Caesar declared himself Dictator, reviving the long obsolete position with absolute power. A decade after the assassination of Julius Caesar, the Roman Republic finally came to an official end when Mark Antony was defeated in 29 BC by Gaius Octavian (aka Augustus Caesar) who believed only a single strong autocrat could restore order in Rome. He dissolved the Republic and became Emperor.

What followed was a period of constant war where the wealth created by the republic was supplemented by wealth stolen from an ever increasing empire of subjugate cities and nations. This continued in violent turmoil and patriotic exuberance until the empire collapsed under its own weight and its pieces lived on in literally 1000 years of war and poverty.

Bastions of Democracy

While most of the world was still stuck in either the oligarchies of the past or in the newer oligarchies in the wake of the Roman Empire, some bastions of Democracy cropped up from time to time, creating enormous wealth for the polities who had them.

The city of Venice in the 700s AD was such an oligarchy. It had limited checks on the Doge’s king-like executive power, who was elected by the Concio, the general assembly of freemen (citizens and patricians). A movement for independence of Venice was gaining steam with a bent toward political inclusiveness. By the time Venice achieved independence in the decade around 800 AD, the city’s economy had shifted toward trade and had grown quite a bit from its position as a fishing village 50 years prior. The patrician class consisted of about 4.5% of the population[11] and, as in Rome, held dominant political power, continuing to do so for centuries despite large increases in political inclusiveness. Venetian citizens were also proportionally few, numbering at about 6% of the population.[18] This meant only about 10% of the population had any representation.

During the mid-900s AD in Venice, the advent of the commenda contract allowed non-patricians a powerful method of upward social mobility through captaining merchant ships and receiving a substantial cut of the profits. Over the next 200 years, political inclusiveness increased as offices and courts limiting the Doge’s power were developed.[10] In 1143 AD, the Consilium Sapientis was created as a council elected directly by the Concio and evolved into the Great Council which had the power to enact law and elect higher magistrates. While politics was still dominated by aristocrats, the increased representation started in 800s created an environment where many more people had upward mobility and say in the political process. Along with this came incredible wealth making Venice possibly the richest city in the world at the time.

In its Golden Age, Venice had a fair number of leaders, moderate representation by the standards of the time, and limited but significant separation of powers. Like most governments before the modern age, there were still few limitations of what the government could do. All in all, Venice was far less representative than the Roman Republic or Athens, but far more representative than any other government at the time.

However, by the late 1200s the new wealthy merchant families, having already climbed to the top, began pressing for barriers to being elected to the Great Council. In 1286, a law was enacted requiring that nominations for the next Great Council be confirmed by the Council of Forty, the Ducal Council, and the Doge, all of which were controlled by the established elites. In 1297, a change was made so those who had already recently served on the Great Council could be appointed without these confirmations. This effectively shut down the ability for upward political mobility. In the next few decades, the commenda contract that built much of Venice’s wealth was outlawed, trade was nationalized, and high taxes were placed on private trading ventures.[10]

Perhaps predictably at this point in the essay, Venice then started on a path of economic decline alongside population decline, and in the 1400s accelerated its imperial tendencies until reaching a territorial peak in the 1450s. Venice languished onward until 1797 when it was absorbed into Austria.

Various other governments involved elections or assemblies, tho like Venice and Greece, large portions of the population were excluded from voting.

Starting in 750 AD, the kings of the Pala Empire were elected by elites and ushered in an unprecedented period of stability and prosperity in Bengal, India. The Iceland Commonwealth founded its Althing assembly, the oldest parliamentary institution still in operation, ushering in 300 years of relative peace and prosperity from 930 AD until Norway absorbed the commonwealth in the 1260s.

The Mali Empire in West Africa was preceded by the Manden Kurufaba, a federation of Bambara tribes that created a constitutional monarchy with the Kouroukan Fouga sometime after 1235. The Manden Kurufaba soon became incredibly prosperous before growing into an Empire larger than any kingdom in Europe at the time before eventually collapsing in 1610.

The Iroquois Confederacy was a federation forged either around 1142 AD or 1451 AD in a heartwarming tale of peacecraft and fellowship resulting in the Great Law of Peace. It was a loose federation with a bi-cameral council requiring supermajorities of male voters and female voters to pass binding treaties. While much is debatable about the date of origin and the actual events of the origin (since the only record is oral tradition), it’s clear that the Five Nations became a dominant force in the area after being formed. There is evidence of massive territorial expansion from future New York into Ohio, Tennessee, Kentucky, and possibly as far as into Eastern Canada. In the early 1720s, Tuscarora fled North Carolina to join the federation making it the Six Nations. The federation broke down and lost of its influence during the American Revolutionary War after they had already been weakened by disease when the nations chose different sides to support. After the war, the federation reformed and had many struggles, but continues to exist to this day.

Between the late 1400s and early 1600s, the independent city of Sakai grew to be the wealthiest city in Japan while being governed via oligarchical elected councils who elected leaders described as being like consuls in Venice.[16][17]

The Republic of Cospaia was an independent city from 1440 to 1826 on the Italian peninsula, that had very minimal governmental institutions. A council of elders and family heads met and occasionally voted to banish a resident causing problems in the community, but basically no other governmental institution existed. The city became a haven for smuggling, refugees, and contraband, including tobacco which was outlawed in the rest of Italy.

The Zaporizhian Sich, aka the Cossack Republic, was created in the 1500s and was able to remain partially autonomous despite the attacks of many neighboring empires for about 200 years. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth established elections for king in 1572, reaching its golden age in the early 1600s and lasting until 1768.[12]

Holland between 800 and 1400 had a period of significant relative freedom that eventually lead to the wealth and power of the Dutch Empire in the 1600s and 1700s. Read more in my more recent post about this.

Conclusion

Venice and the Consilium Sapientis showed that wealth can be created very quickly when moves toward real democracy are made. It also shows how long that wealth lasts far beyond the golden years of a Republic. In fact, Sparta, Rome, and Venice all show this. As I’ll talk about in an upcoming post, even England’s empire shows this, as things fell apart everywhere where democracy wasn’t active.

Sparta only retained reasonable representation for 100 years, but lasted as an independent state for over 400 years. The Roman Republic had about 200 years of good representation before devolving into an aristocracy, and its wealth gave rise to an empire lasting in total from the beginning of the Roman Republic, either 1000 years to the end of the western Roman Empire, or 2000 years to the end of the eastern one. Venice had limited representation for about 500 years, and that wealth lasted it for 1000 years in total. The life of Athenian democracy seems to have been cut short in comparison. There was no clear devolution of its republic in its 250 years – essentially all of those years part of its golden era. If Athens hadn’t refused to join nearby federations, it may have had another 1000 years of independence.

Seemingly without exception, all of these areas with representative governments became rich, and then used their wealth to engage in massive empire building. As I’ll talk about next post, this pattern continues into the modern age. Perhaps, tho, it’s simply what ruling elites do when they’re presented with unprecedented national wealth, rather than something related specifically to representative government.

Late-stage Athens and most of the years of the Roman Republic had a higher-than-majoritarian level of agreement needed for laws, but the level of agreement needed for constitutional change was much lower than in modern governments. This property made the structures of these ancient governments unstable and in constant change.

The monarchies and oligarchies that have dominated the governmental landscape since the dawn of time are so strong a force that they pulled these early democracies apart. In almost every case, the democracy was undermined from within by elites trying to solidify their own power.

While rising representation isn’t a requirement for a powerful nation, it seems to be an incredibly effective way of building prosperity. There isn’t consensus on whether the actual representative governmental structures are what causes prosperity – it may be that a winnable struggle for better representation is what causes prosperity rather than the resulting structures being the root cause. For example, in cases like Venice, the inclusive economic institutions predated the inclusive political ones. But it seems clear that rising representation correlates very strongly with economic prosperity.

Not only that but, to mirror the vicious cycle of exclusivity that drives oligarchies to consolidate, there is a virtuous cycle of inclusivity that drives societies of a certain inclusiveness to become more inclusive, not only because of momentum but also because inclusive political institutions lead to inclusive economic institutions and vice versa. At a certain point, it becomes more valuable for members of a large oligarchy to bring more people into power than it is to consolidate power. After all, its much more dangerous to be a member of a small oligarchy than a large one.

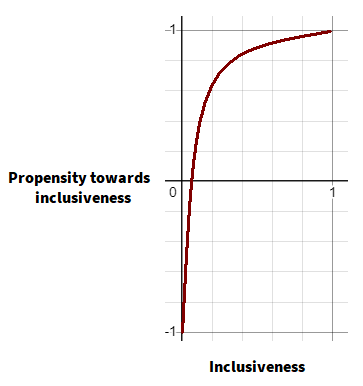

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson talk about this virtuous cycle in their book Why Nations Fail. I like to call this the valley of inclusiveness:

Below 0, there are forces making the society less inclusive. Above 0 the opposite is true. Changes in inclusiveness operate on the scale of decades and centuries, and much volatility generally happens in the meantime. However, this is why I’m optimistic that our current world stage of falling inclusivity is a blip in a longer term pattern of rising inclusivity.

In a post coming soon, I’ll continue this history in the modern age, discussing nations that haven’t yet fallen.

References

2. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sparta

3. http://classroom.synonym.com/different-institutions-greek-democracy-9685.html

4. http://www.stoa.org/projects/demos/article_areopagus?page=all&greekEncoding=UnicodeC

5. Ancient Sparta: A Re-examination of the Evidence, Issue 84 by K.M.T. Chrimes page 488

6. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Peisistratus

7. http://www.britannica.com/topic/consul-ancient-Roman-official

8. http://elysiumgates.com/~helena/Government.html

9. Rise of Rome by Anthony Everitt

10. Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

11. https://cassio-nation.wikispaces.com/Life+in+Venice+during+the+Renaissance

12. Political Science for UPSC Mains 2010 page 7.10

14. Italian Manpower, 225 BC — AD 14, Oxford, 1971 by P. Brunt

15. Servus. Rome et l’esclavage sous la République, Rome – Paris, 1987 by J.C. Dumont

16. The Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History edited by Peter Clark

17. An Introduction to the History of Japan by Katsuro Hara

18. Venice in Environmental Peril?: Myth and Reality By Dominic Standish

19. http://www.fsmitha.com/h1/hell04.htm