I had a conversation with my sister about one of my recent posts about welfare and it became clear that we have very different ethical philosophies. Interestingly we both called our own philosophy “utilitarianism”. We couldn’t be both right, could we?

Ethics

Ethics is the study of right and wrong, good and bad. The three major types of ethical theories are deontological, virtue ethics, and consequentialism.

Virtue ethics and deontological ethics are closely related in that they both are concerned with a set of behaviors. While virtue ethics focuses on the internal “good” or “bad” dispositions of a person that lead them to do more “good” or “bad” actions, deontological ethics focuses on the “good” or “bad” actions themselves. It seems clear to me that deontological ethics is a more fundamental form of ethics than virtue ethics, since virtue ethics itself seems to rely on the notion that certain actions are “good” or “bad”, as it defines a “good” disposition to be one that leads to a person doing more “good” actions than one without that “good” disposition.

Consequentialism focuses on the consequences of actions. Similarly to the above, consequentialism seems to be a more fundamental form of ethics than deontological ethics, since a “good” actions usually lead to “good” consequences. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t be good actions. Certainly an action can be considered “good” even if the outcome is not, as long as one would have expected that action to lead to a good outcome. Life throws curve balls sometimes.

Because of the above line of thinking, I am a consequentialist and I claim that everyone deep down is a consequentialist. Some consequences are better than others, and we all should strive to be people who do actions that lead to better outcomes. Regardless whether you think focusing on personal virtues or good actions will achieve those outcomes, the outcomes are still what is important.

Consequentialism

All types of consequentialism have two important aspects:

What is being optimized?

Who is it being optimized for?

Generally what is being optimized is called “economic utility” or often simply shortened to “utility”. Different people have different ideas about what utility is, but the concept stands for outcomes a person prefers in life, whether its “pleasure”, “happiness”, “satisfaction”, “well-being” or various other near-synonyms. But utility might be different portions of all these things for each individual. Some may care more about base pleasure and some care more about intellectual satisfaction. But utility is used to abstract these things away and give people a universal measure of their well-being and the quality of their living experience.

There are of course other things you might optimize for. Maximum personal freedom, maximum population growth, maximum health of a state, etc. But even these seem like indirect goals likely to be ultimately justified based on the quality of lived human experiences that these things (freedom, population, or a healthy state) would promote.

The term “utilitarianism” specifically refers to the idea that it is everyone equally (by some definition of equality) whose utility should be maximized. By contrast, ethical egoism says that one should only see to their own well-bring, and that anything done that helps other people should only be done for things that benefit oneself, like status, returns of favor, or simply the pleasure of helping others where one can find it. An ethical egoist says this is not only ok, but good. But it is by definition not a holistic philosophy, it is a philosophy an individual applies for themselves and says nothing about what outcomes are good for the world at large. It seems to me this philosophy fails because of this in comparison to holistic philosophies. However, many ethical egoists (and many who subscribe to the Austrian economic school of thought) believe that one cannot measure the well-being of others and so everyone seeing to one’s own well-being is the best we can do. Well, I disagree that we can’t measure the well-being of others, we can and do frequently to some degree of accuracy, for example in court rooms and when negotiating what kind of pizza to get among friends.

Ethical altruism is more of a holistic view, but its the diametric opposite of ethical egoism. Rather than focusing only on oneself, ethical altruism advocates that a person focus solely on others without regard for themself. Despite the fact that it is a theory unlikely to be widely practiced by actual people with their own concerns, it comes close to utilitarianism in some situations whenever others are affected at least as much as oneself. However, in situations like the decision of what I should get for lunch, ethial altruism would surely utterly fail because it excludes the party most affected by that decision: you.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is by far the most common ethical framework and almost certainly the most evolved in terms of how much deep philosophical thought has been put into it. From its roots in Ancient Greek theories of eudaimonia and hedonism (which actually advocated the idea that direct pursuit of pleasure is generally counterproductive) to Jeremy Bentham, Francis Hutcheson, and Hume in the 1700s, to John Stuart Mill in the 1800s, and many others.

As far as I can tell, utilitarianism is a complete ethical theory that properly considers the preferences of individuals without falling victim to moral relativism. Some disagree that it makes sense in all cases while acknowledging that it gets pretty close. This is why I’m a utilitarian. It allows taking a situation, a choice, and all their consequences and allows you to clearly and decisively say which choice is “better”.

But what is “better”? What is “good” or “bad”?

If we’re talking about outcomes (consequences), nothing can be said to be “good” or “bad” without knowing what you’re comparing it to (moral realists notwithstanding). You cannot ask “is it good that Alice was satisfied with the outcome?” without a second situation to compare it to. In other words, there is no good and bad, only better and worse.

The apple universe

This brings me back to my conversation with my sister. She believed my analysis didn’t care enough about the poor and cared too much about the rest of us. When we discussed utilitarianism and it came up that there was such a thing as “total utilitarianism” vs “average utilitarianism”, I took the “total” version and she claimed the “average” version.

As an aside, total utilitarianism attempts to maximize the total utility of humanity or the universe of sentient creatures, or perhaps creatures of all types. But average utility seeks to maximize the average utility of the beings in question. With a given population, this is identical. However, it has differences when you consider the affects of bringing new life into the world or ending lives. Total utilitarianism prefers a world of 1 trillion people with marginal happiness of say 10 units to 1 billion people with very high happiness of 1000 units. Some call this “repugnant”, tho I would say repugnant does not necessarily imply that its wrong. Average utilitarianism seems to have more substantial problems, for example, killing the people with the lowest utility would surely raise the average, but that seems substantially more repugnant.

Regardless, in order to test our moralities, I came up with a thought experiment.

You and I are the only people in the universe, we were created just for this purpose, we will be given an apple and decide what to do about it, we will enjoy the apple (or not) and then wink out of existence. However, I only enjoy the apple a little and gain only 10 utility from it while you enjoy apples more and gain 100 utility from eating it. Furthermore, this utility is entirely linear, in that eating 1/10th of the apple gives me 1 point and you 10 points without any diminishing marginal utility along the way. What is the best way to split the apple?

The consequences are bound very neatly in a short time span with a very finite number of people. No need to worry about long term effects or tricky complications. A nice and neat test.

From a total utilitarian perspective, the right answer is to give the whole apple to you. You’ll enjoy it much more than I will.

But my sister in this situation was the “you” that enjoyed the apple more. Her answer was to give me 90% of the apple so that we would both have the same amount of enjoyment from it! It seems my sister isn’t an average utilitarian, but rather a min-max utilitarian. She wants the person who is worst off to have the best possible outcome.

But when I framed the question a different way, I got a different answer. Instead of “me” and “you”, it was two other people. Neither me nor my sister are one of them, but we get to decide their fate. What is the best way to split the apple then?

To me the obvious answer is simple: same as the first way. Me nor my sister deserve anything more or less from a moral standpoint than any other person winked into this universe for the sole purpose of enjoying a bit of apple. Whether its me, or my sister, or you, or someone else doesn’t matter.

But for my sister, she decided instead to split the apple in half and give a half to each person. It seems her morality was relative to her participation. She would choose to sacrifice herself for someone else’s good but not sacrifice someone else. At this point the conversation was getting a little heated, so we didn’t continue probing this line of thought. But it was very illuminating to me.

What morality is deciding to split the apple half and half regardless of the preferences of the individuals? It’s a morality around equality of opportunity, whereas the 90/10 apple split was more like one of equality of outcome. However, equality of opportunity in this case has nothing to do with utility or the preference of individuals. It is instead simply maximizing the equality of opportunity. In the real world, one might expect that equalizing the equality of opportunity might also get close to maximizing total utility, because those who are better at using their opportunity will, over their lives, gain more power and ability to improve their lives and the lives of those around them.

However, in the contrived apple scenario, it was defined that there will be no follow on effects like this, so the only thing that matters is the enjoyment of the apple in the moment. There will always be differences like this between simplified thought experiments and the real world. But this doesn’t make the simplified thought experiments useless. Quite the contrary. It allows us to think through more precisely what we believe to be true. I believe that splitting the apple evenly in general real world cases is likely to in fact be better, in that its more likely to lead to better outcomes of total utility. But this is a rule and not a case. In reality, we don’t generally know people’s preferences with the degree of certainty to make decisions like that, and we certainly don’t generally think about all the long term effects of policy decisions as they will play out over decades or centuries. In the case of the apple in our thought experiment, it seems clear to me that such a rule is suboptimal.

Moral priorities matter

When considering policies according to their expected consequences, having a clear idea what priorities your morality has can tell you which consequences are better and which are worse, so you can choose the policies that result in those better consequences. Relying on gut feelings and intuitions often leads you astray. Having thought through principals allows you to transcend your emotions and instincts to settle on a more accurate truth.

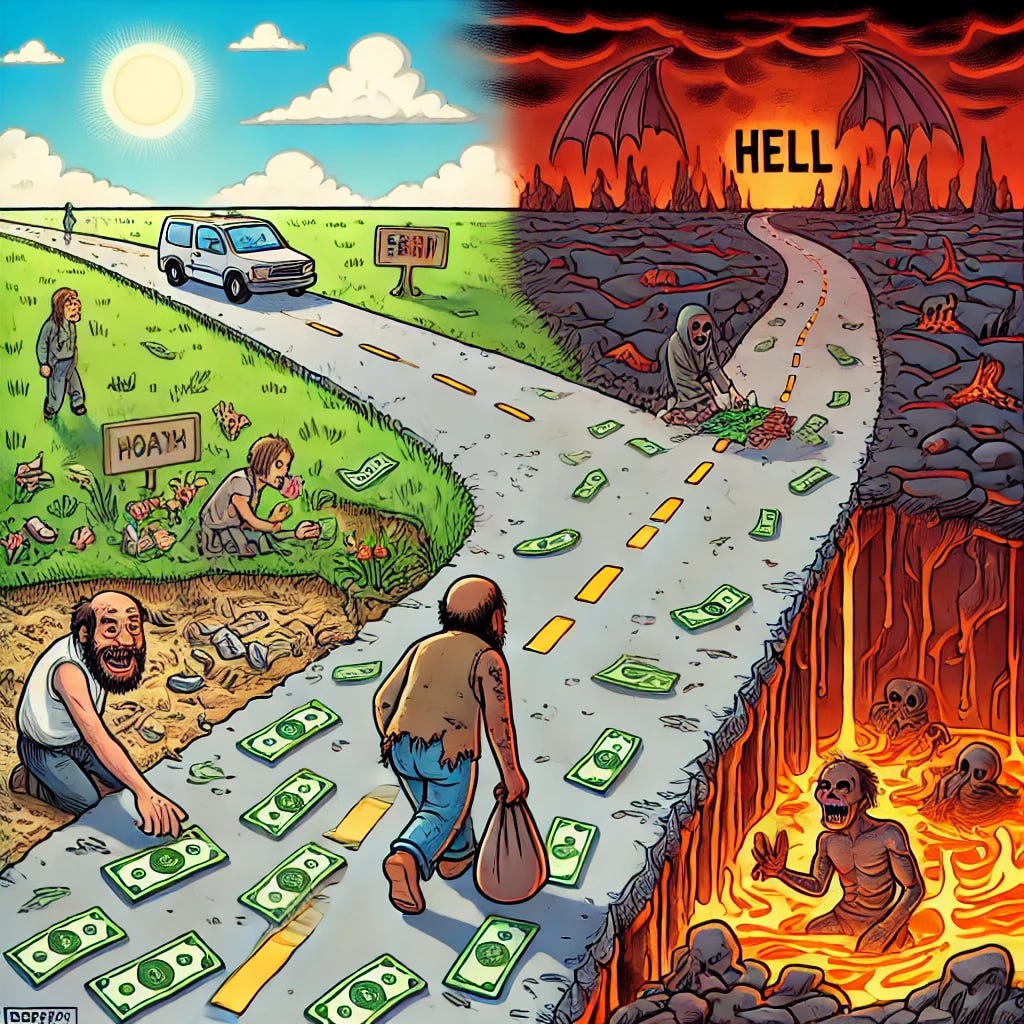

It seems to me that actual min-max utilitarian policy would be a disaster because it would borrow as much from the future as possible to prop up today. On historical time scales, people’s lives have gotten easier and better as time goes on. If this continues into the future, a min-max utilitarian policy would basically advocate for redistributing as much wealth as possible from rich to poor without causing greater poverty in the future. The ideal result of such policy would be a complete stagnation of progress. Poverty would be reduced to some degree and then stay that way forever. The least happy and/or poorest people would be massively better off than before, but at the cost of relegating uncountable future generations to that level of income.

Total utilitarianism on the other hand advocates for economic progress as a tide that raises all ships. While its possible that total utilitarianism might call for giving more to people who are better at being happy, in practice because of diminishing marginal utility, its actually likely to call for giving more to those who are worse off, similar to more altruistic moral philosophies.

Average utilitarianism, while potentially having weird consequences for population control, would realistically probably advocate for most of the same things as total utilitarianism, since economic progress is generally good both on average and in total and killing the poor seems likely to have spill over effects that affect average utility. It seems unwise to give your government a taste for human blood.

Maximizing equality of opportunity seems likely to be often but not always aligned with total utilitarianism, and so does maximizing freedom. Only by thinking through the long term consequences of actions and policies can we appropriately evaluate them.