The Role of Government: Part 1

“The care of human life and happiness and not their destruction is the only legitimate object of good government.“ —Thomas Jefferson, 1809.

Everyone in the modern day can agree that the appropriate role of a government is only to make things better for its people. But what is “better” and how do we know government can accomplish that?

In any society, there are only two sources of action. The first is free activity of individuals, including the market. The second is activity of individuals acting as agents of a government. Voluntary cooperative action in the free market is a very successful mechanism that naturally manages resources. And yet there are certain areas in which the free market has problems, the most significant of which are called market failures. Clearly the only appropriate role for government is to improve on natural cooperation by correcting these failures where possible.

I apologize in advance for the sheer amount of definitions and economics concepts in this post. I have to build a strong foundation of these concepts before I can hope to convince you of my conclusion – a specific and complete definition of the appropriate role of government. So if you feel your eyes starting to glaze over, I swear it’ll be worth it.

In the 1200s, when Thomas Aquinas wasn’t being attacked by local pigeons, he spent time thinking about government. He believed that “a good government is one that protects its citizens from violence.” I think anybody would be hard-pressed to disagree with him. In a situation with no authoritative government, the free market breeds little mini-governments who all exert their authority haphazardly. Disputes often become violent when one mini-government disagrees with another. This is easy to see in a place with weak central government like Somalia, or in situations where government is absent like in black markets. In situations like that, violence is common and those who are most violent are often the richest.

So the rise of violent mini-governments is one major market failure – and it’s a pretty clear fail. Dispute resolution is an area where the market solution is to create a government. People want an authority that can peacefully resolve disputes, as I stated in my first post. But violence isn’t the only market failure.

So what is a market failure exactly?

Market Failure

There seems to be a wide range of misconceptions and incompatible ideas about how market failure is defined. Some seem to think it’s when the quantity demanded doesn’t equal the quantity supplied (ie when there is a shortage or a surplus). Some seem to think it’s anytime the market isn’t perfectly efficient. There also seems to be an undercurrent that any deviation from the neo-classical ideal market (where there is perfect competition and everybody knows everything) is a market failure. All of these definitions are incorrect. This Crash Course video has some misleading information, but mostly well-explains how economics students are taught about market failure today:

In David Friedman’s words, “market failure describes those situations where individual rationality does not lead to group rationality, where if each person makes the right decision for himself, the result is less good for [the group of] people [in total] than if everybody had done something else.” – Listen to the full lecture here.

An example of this is any time you see some jerk stuck in the middle of an intersection after their light turned red or driving slowly in the fast-lane on the freeway. The Ferrari stuck in the intersection will to get to its destination faster by getting stuck in the intersection than by waiting for the light, and the slow Prius in the fast lane has an easier time driving in a lane where no one is in front of it. But it’s not only jerks who cause market failures.

Gordon Gekko’s famous line was “greed is good”, but a more accurate rephrasing is that self-interest can be harnessed for good. Everyone looks out for their own needs for food, comfort, and general happiness as well as the well being of their friends and family. All of that is encompassed in “self-interest”, which drives people to cooperate with each other to produce and invent things that will increase the happiness of everyone involved. This has been incredibly good in the long run, as can be shown by various worldwide statistics about ever lowering rate of violence and war, starvation, and poverty. But self-interest can also be harnessed for ill, intentionally and unintentionally, and that’s what market failure is.

To be very specific, given a particular economic environment, market failure is a situation where the motivations of market-actors incentivizes behaviors that prevent the market from eventually reaching maximally efficient activity, or incentivizes behaviors that prevent the market from eventually reaching the maximum possible rate of efficiency increase.

And by “economic environment”, I’m talking about a situation where people know of certain technologies and techniques, and where there are certain behavioral patterns people follow either because of social pressures or government.

A market failure is a much stronger notion than simple inefficiency. It’s not about whether there is inefficiency in a given economic environment (its a certainty there always is), but rather about whether that inefficiency can be reduced toward zero in that economic environment. In economics, the place on the efficiency scale a economic environment tends toward is called the equilibrium of that market.

This definition means that the normal and temporary inefficiencies that occur in real markets, where effects are never propagated instantaneously, aren’t market failures on their own. This includes things like market inefficiencies from lack of knowledge, conflict of interest, and various other things I’ll talk about further down. Market failures might cause these kinds of inefficiencies to become chronic, but their existence isn’t sufficient to call the situation a market failure.

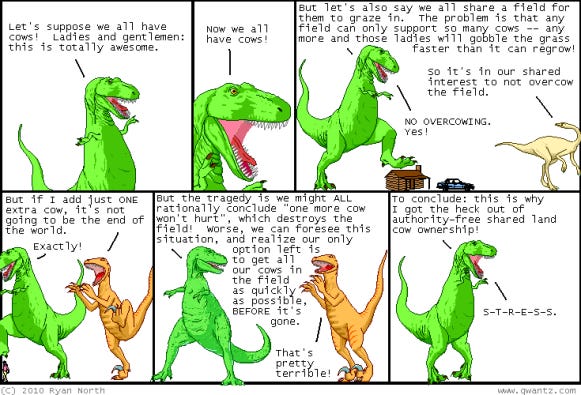

Also, a market failure that happens in one economic environment may not happen in another. For example, before the widespread use of enclosure acts in England in the 1700s and 1800s, large parts of England were designated as “commons” that could be used by anybody. While they were sometimes organized by local committees, there was a lot of limitation for what could be done on common land and abuse was… common. This abuse has been made famous by the term ‘tragedy of the commons’. When enclosure acts privatized this land, it changed the economic environment to make possible a wide range of innovations that helped increase agricultural output and other sectors in England immensely. In this case, it was change in law that changed the economic environment. Technology can also change the economic environment as things that were impossible become possible.

The last piece of this puzzle is that when progress toward market efficiency is systematically slowed, that’s also a market failure. While such a market may eventually get to maximal efficiency, it may take so long that a lot of potential efficiency is lost. That’s the point of including the bit about rate of efficiency increase in the above definition. For example, a monopoly still has incentives to sell and improve their product, but those incentives might be substantially less than what exists in an industry with a competitive market.

Efficiency

It feels like this article is going to get filled up with definitions, so I might as well get it over with. One thing still left vague is what “efficiency” is. What is “maximally efficient activity”?

This necessarily gets into the concept of economic utility, which is how efficiency is quantified. Economic utility is a measure of the value a person gets out of some item or activity. Any action a person takes has costs and benefits to that person’s utility. The activity in question can be buying and selling goods or providing a service, but can actually be anything a person can do, like relaxing on the beach, giving to charity, or browsing the internet.

A higher utility for a given person means they are “better off”. Because this is still pretty vague, so for the purposes of this blog I’ll be treating economic utility as a measure of a person’s current happiness. But a person doesn’t generally just want to maximize their current happiness, they want to maximize their happiness over their whole lifetime.

A maximally efficient economy is one where the sum total of all the future utilities of the people in that economy is on track to being maximized – essentially to maximize the total happiness of everyone. Maybe this is the true meaning of life: to help humanity maximize its total happiness over the course of its existence.

A related measure of efficiency is something called Pareto efficiency. The above image shows a number of economic states (the circles) between two people. Via the free market, various trades these two people make can increase total utility with the rule that trades will only happen if both parties gain from it. This leads to what is called a Pareto optimal state, where no other state can be moved to without making someone worse off.

In the above picture, the blue circles are all Pareto optimal states, and the set of all those blue circles is called the Pareto frontier. So if the state is at X, it can move to Y, which is more optimal. But a free market will never move to state Z from X, because Person 1 would be made worse off from that change.

It’s important to note that not all Pareto optimal states maximize the utility of the system. For example, while states H and G are both Pareto optimal, it’s clear that state G is more optimal overall since by moving from H to G, Person 2 would gain more than Person 1 loses. However, the free market will never make such a change. While not all Pareto optimal states maximize utility, the states that do maximize utility will always be Pareto optimal states. I’ll talk about how this relates to welfare programs further down.

You could imagine this graph extended so that every person gets their own axis (3 dimensions for 3 people, 4 dimensions for 4, etc). But regardless of the number of people, the concept remains the same.

In any case, lets get back on the topic of market failures, because the concept is super important, probably the most important concept in government since it is the guiding principal for both policy decisions and constitutional limitations of governmental power.

Types of Market Failure

I’m going to argue that there are only three categories of market failure: externality, anti-competitive markets, and sub-optimal Pareto optima.

Externality

“The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individual or collectively, in interfering with any of their number… the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good.. is not a sufficient warrant.” – John Stewart Mill

John Stewart Mill was talking about externalities in his quote, which is the most important concept when discussing market failures. An externality is a cost or benefit (not including those propagated via changing prices) incurred, as a result of a voluntary action of one person or group, by a someone who didn’t agree to that action.

Now there’s a lot in that little definition so let me break it down with some examples. One classic example of a negative externality is the tragedy of the commons I mentioned above.

Every additional cow using the field means less useful field, which puts a negative externality on everyone.

So why does externality happen? The reason is fundamentally about transaction costs, the costs necessary to enforce property rights. In the cows’ case, it might very well be feasible to identify who’s putting how many cows in the field. Coasian bargaining could then be used to resolve the externality (to “internalize” it).

But in the case of pollution, it would clearly cost more for someone to personally identify all the drivers who are polluting their air than they could hope to receive in return. And so the rational choice is to ignore the pollution – to just let it happen.

While its obvious why negative externalities aren’t good, its perhaps less obvious why positive externalities aren’t good. In the classic example of a home’s front-yard garden, passers by benefit from the nice view. This benefit to the community is a good thing right? Well yes, but the fact that there’s an externality here (that passers-by can’t feasibly be charged for their enjoyment) means that that good thing will be under-produced. People might put a bit more effort into making their gardens nice if they were getting paid for it. If it were cost-effective to eliminate the externality by charging for viewing the garden, more of that good thing would exist.

To illuminate why it’s important to exclude costs and benefits propagated via prices, we’ll take the example of a donut shop. If a shop is selling cronuts, for example, they’ll set a price and people who want cronuts will buy it from them. If a new bakery opens up nearby that also sells cronuts, it’s likely the first bakery will start making less money either because they will sell fewer cronuts or because they have to lower the price of their cronuts (or both). While this makes that first bakery less well-off than it was before, this is not an externality because it happens through the price system – which is fair game. It also means more, cheaper, and probably better cronuts for everyone.

Violence, the first market failure we identified, is an example of an externality. Whenever someone attacks another person or steals their things, that’s a negative externality because the victim didn’t agree to be beat up and robbed.

Another thing that can be considered an externality is fraud, when someone entices you into an action by lying. While this falls into the category of information asymmetry, it also falls into the category of externality. Imagine someone left a time-bomb on your doorstep. This is an obvious case of externality – the cost to you is that you have to spend your time calling the bomb squad and the associated stress. And of course the risk of your house blowing up. Fraud is like a time-bomb. You are given some misinformation that can then metaphorically blow up in your face when you use it to make the wrong decision. If you never end up using that information, it is like a dud time-bomb – by chance it doesn’t affect you. But there was still risk that it would. So by this logic, fraud is also an externality.

I should also note something I’ve never seen written. The actions of a government are *always* externalities. By definition, a government sets up rules that affects those who aren’t government agents without their explicit permission (even in a democracy, you might not have voted for something). The way a government corrects for a negative externality is by introducing a positive one, and vice versa. It’s important to realize that it isn’t possible for a government to make a market perfect. It can only balance market failures by in essence introducing another market failure in the opposite direction. If policy makers aren’t careful, this can lead to situations where government externalities remain in place after the economic environment removes the market externality. This is one area (tho not the only one) where what was once good government policy becomes bad over time.

Monopoly Misunderstood

Possibly the most controversial type of market failure is the anti-competitive market: a market of monopolies and oligopolies. Since oligopoly is basically analogous to monopoly, I’m just going to talk about monopolies as being representative of anti-competitive markets.

A monopoly is a situation with net economies of scale are increasing near the quantity the market demands, ie where marginal cost divided by marginal value decreases. In such situations, the larger the company is, the more efficient it is at producing its product and a second company would not be able to compete (or in the case of oligopoly, perhaps 3 companies can survive but a 4th can’t compete).

An anti-competitive market doesn’t necessarily arise from anti-competitive behavior of companies. It can happen simply because of the nature of the product (although as I’ll talk about soon, monopolies usually happen because of government interference). It might happen where there are network effects that cause the value to each user going up with number of users. Or it might happen because of costly barriers to entry that are less costly per unit produced as the units produced goes up, for example when small companies must pay the same cost as large companies for entry into the market, or when new entrants must pay costs the incumbents didn’t need to pay when they entered the market.

Coercive monopolies (ones that keep their position using extortion, violence, government enforcement, etc) obviously always involve externalities, and so can be understood in that context without any additional concepts. Natural monopolies, on the other hand, occur in situations where cost per unit of a product significantly drops or value per unit significantly rises as more customers are served.

I was going to write a full analysis about natural monopolies in this section, but it became a bit too long and distracts from the role of government. So I’m going to write a future post about monopoly instead and just summarize my conclusions here.

I concluded that there isn’t likely any significant tendency toward the dead-weight loss that intro econ textbooks frequently talk about, and any additional profit a natural monopoly makes over a similar non-monopoly company isn’t necessarily a problem in the economic (or real) sense. Economics PhD Stephen Shmanske wrote a solid paper called The Monopoly Nonproblem on the subject of how the dead-weight loss theorized by introductory economics is unrealistic because of the practical use of discriminatory pricing.

However, there’s still a problem. A true monopoly by its very nature means competition is kept out by some economic barriers, even when monopolies don’t use anti-competitive practices. While this is identifiable as a possible inefficiency, it is not an externality, because it operates through the price system. The natural monopoly is able to naturally outcompete its competition, and so just like opening a competing cronut shop don’t cause externalities, monopolies don’t either. One additional fact that leads to the same conclusion: because a monopoly already sets it price higher than the price that would achieve optimal total utility, attempting to tax a monopoly for the “cost” it imposes on competition would only increase that price and increase (rather than decrease) the theoretical deadweight loss.

Interestingly, Joseph Schumpeter recognized that the relatively high producer surplus that monopolies gain gives them a higher than normal incentive to innovate in their market, because they can capture a much higher fraction of the value created by that innovation. So while the lack of competition is a downside, it might be made up for by increased innovation. The dynamics here are far from well understood however.

Its important to realize that in judging whether a company is “keeping competition out”, a realistically achievable alternative market structure must be the bar to judge by – not some imaginary and unachievable perfect market. While a natural monopoly may naturally prevent some competition because of the difficulty of competing, the alternatives to natural monopolies usually suggested should not be expected to be more socially optimal than the natural monopoly itself. Nationalized monopolies are still monopolies, but with the added inefficiency of lacking proper incentive mechanisms to limit costs and produce value for their customers. Regulated monopolies have a similar problem, as public choice theory predicts, the regulation should not be expected to be in the best interests of the customers of the monopoly, and often ends up making it even more difficult for competitors to compete with the monopoly.

I should also mention that most companies that people think are natural monopolies, aren’t. It simply isn’t sufficient for a company to be dominant in a market. In fact, even most situations where only one company sells a product of a certain type aren’t cases of natural monopoly. In practice, natural monopolies are actually rare to find. Where one comes up, competitors tend to follow, making the situation an oligopoly and not a monopoly. Even a small number of competitors can be enough competition to lead to a trend of significant improvement over time.

For example, Microsoft still dominated the personal computer market in 2007 with over 95% of personal computers being sold by them. Even today when that number is less than 20%, PC remains synonymous with Windows. But they have never been an example of a natural monopoly. Any company who wanted to create a competing operating system could write one that runs Windows programs. Yes it would have been difficult, but its possible and in fact has been built by open source programmers working for free in the form of ReactOS and Wine among others, not to mention competing operating systems like MacOS and the many flavors of linux. Another example is the area of search engines where Google is dominant and yet there are a good many alternatives surviving in the market.

Even with more classic natural monopolies, competition still naturally arises as long as government doesn’t put legal barriers in the way of prospective competition. An example is the rail system in Japan, where many competing train companies offer services in a way that is a little confusing at first, but works quite well once you get used to it. Its only the government protected monopolies where competition doesn’t arise. I’ll mention more examples in my future post about monopolies.

I also have a novel solution that could substantially increase competition in traditionally monopolistic markets that I’ll propose in my future post, but for now we can leave it that natural monopolies don’t likely cause significant market inefficiencies and don’t generally result in inadequate competition.

Sub-optimal Pareto Optima

Remember how I mentioned that not all Pareto optimal states maximize total utility? Well that’s where starting conditions come in. It stands to reason that different starting conditions can lead to different results, and this is true in the economy. If not all Pareto optimal states maximize total utility, then the market isn’t likely to get there no matter how far or close that Pareto optimal state is to a globally optimal state.

There isn’t much more to say about that in this section, except that some economists take the position that it isn’t “the place” of economists to determine which state is ideal, but I and others disagree. I’ll talk about that next post.

Imperfect But (Pareto) Optimal

Despite how important the concept of market failure is, it is generally poorly understood and misused, intentionally and unintentionally. To make sure we know that the above two categories cover all the things that are market failures, we need to know the conditions where there aren’t any market failures.

I propose that there are four properties of a market that are necessary and sufficient to lead it to always approach maximal Pareto efficiency with maximal speed:

Well defined and upheld property rights

A sufficiently large number of potential market providers of a substitute for a particular good/service.

Actors motivated and able to act in their own self interest

Item 1 is essentially related to externalities. If property rights of things like the air you breath were well defined and upheld, polluters would have to pay people fairly for their air that they pollute.

Item 2 relates to monopolies, which also have externalities. The economy operates on a similar basis to survival of the fittest. In biology, creatures evolve depending on random genes that either cause animals to survive and procreate or genes that prevent an animal from procreating. Without a sufficiently large population of a given creature, evolution effectively can’t happen. Similarly, without a sufficiently large number of potential entrants into a market, the economy can’t efficiently function. The varying ideas and approaches people use to compete in a market is critical for innovation to happen and market efficiency to increase. I’ll explain this more further down.

Also note that in item 2 it’s the potential market actors that matter, not the actual number who are providing a certain product. There’s a big difference between people choosing not to produce a certain product and people who are prohibited from doing it.

Item 3 relates to the importance of actors acting in their own self-interest. It’s self evident that all people (and all animals) are motivated to act in their own self-interest. Beyond this, a person must also be able to do so – and this leaves a bit of vague wiggle room for where to draw the line between “able” and “unable” here, but like most situations, there is likely shades of grey rather than a black and white line. Regardless, a good example are babies and small children, who most people agree can’t adequately act in their own self-interest, even tho they are obviously motivated in that way – as any greedy child can attest to.

Now this model is much simpler and has fewer constraints than your usual econ-class situation of perfect competition and the First Fundamental Theorem of economics, and it’s much more applicable to the real world because of it. Transaction costs, imperfect information, differentiated products, imperfect factor mobility, economies of scale, network effects, and irrational actors can all exist while still tending toward maximal Pareto efficiency.

In fact, many of the conditions of perfect competition would be sub-optimal in the real world, because the costs of setting up perfect competition would vastly outweigh the benefits. An example of this is perfect information. There is a cost to getting good information, and a much higher cost to getting perfect information. By treating information as just another commodity with costs and benefits, you can eliminate an unnecessary restriction from the model of economic efficiency. A similar argument holds for other transaction costs.

The price taking behavior usually held as a condition for a Pareto optimal equilibrium has also been shown to be unnecessary in the presence of price discrimination, which happens all the time in real markets.[1][2] I’ll also talk about that more further down.

Some might include what economists call local nonsatiation as a requirement, but I believe that it is not required. Local nonsatiation is the concept where all market actors can always improve their utility somehow (eg by receiving a good or service). The idea is that if market actors are satiated, then no trades will happen and the economy can’t improve. However, I would argue that any market actor who is satiated has basically reached their highest utility and doesn’t need the market anymore. Other market actors will continue trading until they’re satiated. If all market actors become satiated, that’s a pareto optimum. Regardless, in real life, its pretty much impossible for local nonsatiation not to hold unless everyone reaches nirvana and lives as hermits out in the vast wilderness of Canada or if the rapture happens, so it can’t contribute to a theory of market failure and so I won’t need to talk more about this.

Its important to realize that the right way to measure efficiency is to find how close to the achievable optimum the current market is, rather than comparing to some magical theoretical optimum like a perfect market. While perfect competition is obviously impossible in real life in almost any market, the above three conditions can actually exist simultaneously in real markets, and a large majority of markets can get very close to satisfying all these conditions.

So any market situation that chronically prevents one of those three attributes causes a market failure. Any human-created system that exploits poorly defined property rights, restricts the number of potential entrants into market, or causes people to be unable to act in their own self interest are causing externalities and therefore market failures.

Again, the market failure left out of this analysis are ones that stem from starting conditions that lead to the “wrong” pareto optimum. Again, I’ll talk about that next post.

Ignorance, Irrationality, and Inefficiency

We can also look at this from the other direction: all the ways that a particular action can be Pareto inefficient. There are two broad categories: things in a person’s control, and things out of a person’s control.

Of the ways that are in a person’s control, there are two sub-categories:

inefficient actions a person does because of a lack of information (ignorance), and

inefficient actions a person does because of imperfect rationality (irrationality), ie they don’t use the information they have to come to the best decision.

Of the ways that are out of a person’s control, there are also two sub-categories:

externalities: someone else forced them to incur a cost or benefit, and

starting conditions: people started with a particular amount of wealth, which can lead to a globally sub-optimal Pareto-optimum.

Things that a person actively does because of lack of information can cause theoretical inefficiencies, but a person wants to have full information, and thus there isn’t a motivation for chronic market Pareto inefficiency. The market itself can evolve to give people the information they want. The only case of someone’s motivation actively causing a person to have a lack of information is fraud, which I’ve already mentioned is an externality. And finally, actions a person does because of imperfect rationality are very similar: a person wants to know they’re being irrational, but they have to be convinced that there’s a better way to analyze their situation, and that convincing can sometimes be costly enough to make it not worth it. Again, the market can evolve to give people the information needed to convince them of their irrationality if the benefit exceeds the cost.

There are certainly cases where the market will not by itself provide the information people want or the tools they need to come to rational decisions, because the cost of providing that information is higher than can be extracted from the people who benefit from that information. In this case, it may be best solved as a public good – a government produced positive externality. For example, warnings about a rock-fall area might help some people avoid injury, but such warnings are unlikely to provide any revenue for the sign owner.

So by this logic, I again conclude that externalities are the only cause of chronic Pareto inefficiency. And yet again, sub-optimal Pareto-optimum makes an appearance. I’m gonna continue to drag my feet on this point until next post when I’ll talk about the solution to it.

Market Failure Myths

“Its heresy worth considering” – Milton Friedman

There seem to be a lot of cases where vague definitions lead people to incorrectly conclude that a huge variety of things are market failures if anything ever deviates from the magical perfect market. There are also some concepts that are described as novel concepts, but really end up just being externalities. Here are the major culprits:

Myths from the Fantasy of Perfect Competition

A major list of supposed market failures stems from the idea that the only way a market’s equilibrium will reach Pareto efficiency is if there’s perfect competition. But economists have shown that not all the conditions of perfect competition are necessary for Pareto efficiency. And yet many people writing about economics still make this mistake.

One such misunderstanding involve incomplete markets or “missing” markets, situations where nobody is buying or selling a certain product. While a market failure may cause a market to not exist, say if there are high positive externalities, the fact a market doesn’t exist for a product isn’t a sufficient condition for market failure. The product that would be sold in such a market might just be something no one wants. Or people may not know how to create a market or the technology might not exist yet. These issues don’t prevent eventually reaching maximum utility and so aren’t market failures.

Merit and demerit goods are another example. There are two different definitions for both of these things. One definition is something that a person under- or over-consumes because they don’t realize the true cost/benefit of it. This clearly falls into the category of lack-of-information and thus doesn’t cause market failure as described above. I talk about the other definition in the next section.

Time-inconsistent preference, also called a dynamic inconsistency, is when a person’s preferences change over time. This is either a lack of information (about their changing preferences) or irrationality (ie ignoring that they know their preferences will change) and I already described why those never lead to market failures.

Similarly, information asymmetries, where one party knows more than another, has the exact same properties of either being a lack of information or irrationality. This sometimes stems from a situation known as adverse selection, where one party to a transaction withholds information from the other to gain an advantage, but can also be caused by a situation where there may be no cost-effective way to give the buyer that information in a form they will trust.

A typical example of this is buying a used car. The car salesman knows the quality of the car being sold much better than the buyer, because they’ve assessed the car. Because of the buyer’s inability to assess the quality of the car, they are forced to assume that the car is average quality, which makes it not profitable to sell above average cars. In true donkey space fashion, this drives down the quality of used cars that are sold, and as the average goes down, the fewer and fewer used cars become worth selling. The logical conclusion is that only the very worst used cars are able to be profitably sold. A usual solution to this is the warrantee, where the seller will assert the quality of the vehicle and will pay damages if that assertion ends up being false.

Another example from the other side is insurance, where higher-risk customers are more likely to buy insurance. Again, since insurance companies know this, this leads to higher insurance premiums for everyone. While a warrantee could potentially be used for this situation as well, generally the only market solution used here is to require more information from buyers of insurance.

So there are market solutions to information asymmetries, but even when a perfect solution cannot be reached, the market solution cannot be improved upon because of the information costs. Cases of fraud are the only way that information asymmetry can be connected to a market failure, and its the fraud externality that causes that failure, not the symptom of asymmetric information.

Conflict of interest, aka the principal-agent problem, is where a person gives another person proxy rights to make decisions on their behalf and that second person (the agent) is motivated to make decisions that aren’t in the best interest of the first person (the principal). There are a few ways this can happen. One is that the agent misrepresented themselves, which is fraud and an externality. Another is that the principal didn’t know some important info about the agent or misevaluated some info, and made the mistake of using them as an agent. This second case is again the lack of information or irrationality, and so again can’t lead to a market failure. Basically, the principal-agent is important only in micro economics, not the macro economics that I’m talking about in this post. For any given company, that company has full incentive to ensure their employees don’t have conflicts of interest, and because of that there is no market failure.

I’ve also seen factor immobility described as a market failure. Factor immobility describes barriers to moving capital (materials, machines, etc) or barriers to people moving between jobs. In the case of people, one category is occupational immobility, related to structural unemployment, which describes barriers for a person to change to a new type of work. The other category is geographic immobility, which describes barriers for a person to move to a place where they can take a new job. For example, a person who doesn’t want to move to a new country to find a job may value their current network of friends and culture more than they would value the increased salary and satisfaction of a new job in that other country. This isn’t even a market inefficiency – those who say it is are not accounting for the real costs people have to incur to learn new skills or move to a new location. Because it doesn’t even fall into the category of market inefficiency, factor immobility can’t cause market failure. This can be generalized to any kind of good or service by treating those barriers as costs.

The Many Faces of Externality

Externality is so important to understanding market failure because the vast majority of phenomena that cause market failure are externalities. Some writers like to build long lists of market failures. But these lists inevitably cause more confusion than they cure because most market failures talked about are actually just externalities. Erroneously talking about these things as peers of externality, rather than the special cases they are, obscures the essence of market failure. For example, I already mentioned how conflict of interest could induce fraud: an externality.

I also already talked about one definition of merit and demerit goods as something a person doesn’t realize the cost or benefit of. The second definition is a benefit given to, or a cost imposed on, everyone (e.g. basic science research is a common example of a merit good). This is also known as public goods and public “bads”. A public good is just special case of positive externality. A demerit good, where a cost is imposed on everyone, is similarly a negative externality.

Another is indivisibilities and common property. One of the conditions of perfect competition is that goods are “infinitely divisible” such that any transaction is so small that it doesn’t affect market prices and every user of a good uses their own tiny division (so there is never any sharing). An example often given for this case is a public good like a road, where many people use the road and it’s difficult to track exactly how much of that road someone used. Regardless of how possible toll-roads are, any indivisible good must be shared not necessarily with everyone, but with among some number of people. It therefore can have the externalities associated with tragedy of the commons, but that is the only market failure this indivisibility can cause.

Other Myths

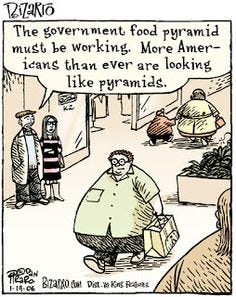

Humans aren’t perfect analysis machines, and so don’t always make the best decisions even when all the information is available to them. Behavioral economists call this an internality. The common example of this is someone chronically eating too much, causing them to develop health issues. This kind of poor impulse control is essentially the result of either a lack of information or irrationality, and so is never a cause of market failure. Even so, some cases may look like an internality, but aren’t. If, for a given person, the utility they get from enjoying that amount of food now is greater than the utility they’ll lose from future health problems, then “over-eating” is a completely rational and optimal decision. Thus this case isn’t even an internality, despite what other people think is best for that “over-eater”. While there may be psychological tricks that improve the lives of us imperfect humans, we should expect people to rationally choose to opt into these tricks if they’re convinced they’re actually in their best interest.

I’ve even seen inequality described as a market failure. While inequality has certainly been shown to be an indicator of systemic problems in the economy, inequality is not always bad, and a certain level of income inequality is in fact a necessary result of an efficiently operating market when the people in the market have different amounts of skills and resources. You can’t expect someone with more valuable skills to earn the same amount as someone with less skills unless you underpay that first person, which would itself cause inefficiency. High levels of inequality is just a symptom of a set of more basic problems. The only case where inequality can be argued as having an objective downside is in the context of a fairness criteria like envy-freeness, in which case it’s an externality (tho that’s very debatable).

Conclusion

I’ve covered a lot of things in a relatively short post, all things considered. I’ve built a case that externalities, anti-competitive markets, and globally sub-optimal Pareto optima are the only three possible market failures and I gave conditions for a realistic Pareto-improving market.

If you’ve made it all the way through, you now know more about macro economics than 99% of the people out there.

The only appropriate role of government is to correct for market failures where the government solution is less costly than the market solution. Market failure is a concept much more specific than usually talked about, and I tried to explain those specifics as accessibly as possible. But this is only half the story. In part 2, I’m going to be much more specific about the appropriate ways the government can correct for market failures. I’ll give a definition that not only defines what conditions a government solution is appropriate, but what possible solutions are appropriate in each condition.