Taxes are often seen as something of a necessary evil. No one likes their money taken from them, and beyond that, taxes generally also cause economic inefficiencies. But we need to fund government somehow (let's avoid anarchist arguments for now).

What if I told you there was a tax that, rather than causing economic inefficiencies instead reduced economic inefficiencies? What if I told you this tax had the potential to be the primary basis for most or all taxes in a country or city? What if I told you this tax might even be able to solve the housing crisis, narrow the income inequality gap between the rich and the poor, and eliminate one of the primary market cycles that cause recessions?

Too good to be true? The economics may surprise you.

What is a Land Value Tax?

A Land Value Tax taxes just the land without taxing things on the land like a building, a well, an orchard, or other improvements. Beyond this, proponents of the land value tax usually advocate for taxing not 1% or 2% of the land's value, but nearly 100%. Why? Well there are various reasons given, both historical and modern. I'll explain my conclusion first before touching on what other people might tell you.

The value of a plot of land usually comes primarily from the things beyond the property line: utilities, parks, businesses, views, people, and any other amenities of the community. Especially in more populous areas, the land itself is often worth many times the value of anything on the land, including houses or even larger buildings.

To paraphrase a story from Henry George, imagine an endless flat uniform land that extends out in every direction where any patch of the land is the same as any other. If the first settlers appears in that land, where do they choose to settle? Well, it doesn't matter, anywhere is just as good as anywhere else. But when the second group of settlers comes along, where do they choose? Do they choose as far away as possible from the original ones? Or do they choose somewhere nearby?

The answer is almost definitely nearby where they can interact with the others, socialize with them, and trade with them to take advantage of division of labor and economies of scale. The land nearer to those first settlers is more valuable than the rest, not because anything about the land itself, but because of its proximity to other people and the fruits of their labor.

So it should be clear that there is a positive externality at play. Most of the value of most land comes from things that are external to the plot of land itself. This is why the optimal Land Value Tax is done as a pure Pigouvian tax: taxing only the positive externalities conferred upon a plot of land.

If you haven’t read my last post with an explanation of Pigouvian taxes, recall that because a properly done Pigouvian tax reduces deadweight losses instead of causing them, the economics can be positive even when the activity the tax funds is *less* efficient than what the tax payer would have done with the money. In other words a Pigouvian tax itself is a productive service for the economy, unlike other kinds of taxes. This of course isn't an excuse to use taxes inefficiently, it just highlights that Pigouvian taxes are more efficient.

The problem with a tax on benefactors of a particular externality is that there’s no market for eg fire protection externalities, and so estimating the externality is inevitably a theoretical exercise. You could say the same for the positive externalities conferred by bee keepers, neighbor’s pretty gardens, or nice looking architecture.

But there is a very clear and direct market for land. And all of these externalities find their way to increasing land value. A neighborhood with lots of pretty gardens and well organized fire prevention will have higher land values because of those things. A land value tax can capture all these geographically constrained positive externalities whether the source is known or not, and with much higher accuracy than could likely be done for any specific positive externality.

But why tax that at near 100%? Well just like the optimal Pigouvian Tax for pollution taxes is at a rate equal the entire externalized cost of that pollution on society, the optimal Land Value Tax taxes the entire value of the positive externality conferred upon the land. 100% is the rate that most effectively corrects the externality. Most Land Value Tax proponents argue for *near* 100% and not actually 100% because taxing more than its worth would result in people willing to pay people to take any undeveloped land they own (among other inefficiencies). So 95% might be close enough.

There are several things that are not standard treatment about how I defined a land value tax. One is that Pigouvian taxes are usually defined as a tax correcting a negative externality. We're just going to ignore this and call it a Pigouvian tax anyway, even tho the externality involved is positive and not negative. Or if you really need a new name for it, call it a Tidroudian Tax if you must.

The second non-standard thing about this is that a land value tax is usually defined as a tax on everything except the human-built improvements on the land, while I defined it in terms of externalities. Traditional Land Value Tax proponents advocate taxing a property that contains valuable natural assets higher than other land. This might be valuable minerals, a beautiful waterfall, explorable caves, a natural pond, etc. However, because none of those are externalities, it is not efficient to tax them like it is for the external value of the land. I’ll expand on this later.[10]

Land Value Tax before and after Henry George

Between the 800s and 1100 CE, various places in Europe followed the Danegeld model of a land tax based on a unit of area called the “hide” as a way to collect tribute to or protection from Viking raiders. These were often high taxes that were exacted in unfairly discretionary and unforgiving ways, earning them widespread dislike. A huge amount of land was confiscated, as much as 2/5ths of all English land during the right of King William in the late 1000s. This lead to basically all land being owned by lords rather than peasants, which accelerated the proliferation of feudalism and the manorial system in England. The strife even spawned the legendary story of the Lady Godgifu (aka Lady Godiva) riding naked through the streets to save her subjects from the English Heregeld.[1]

It wasn’t until the 1700s that significant thinking was done about taxing land value. The economic theory known physiocracy, which originated in France, resulted in many economists known as physiocrats advocating for the land value tax as the only tax that should be levied. As a result of Physiocrat movement, taxing land value was implemented in France and Denmark in the late 1700s and mid 1800s respectively.

Thomas Paine and Thomas Spense both advocated for a land value tax as well as a citizen’s dividend from it. Adam Smith noted that the land value tax did not result in deadweight losses and could not be passed on to tenants. John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson were also all advocates among many others.

Henry George is the most historically famous advocate of the Land Value Tax, and also advocated it as the only tax that should be levied, calling it The Single Tax.

Henry George noticed that places that had undergone the most progress and productivity also had the most stark poverty. Big wealthy cities would have people poorer than the poorest people in small poor towns. He himself had been quite poor in San Francisco, saying that in at least one instance he had been desperate enough that he might have killed a man for money if the man had not given it of his own accord.

When he visited New York City, he was struck that the poor were worse off than those in San Francisco which was much less wealthy at the time. Later in San Francisco, he was again struck at the high price ($1000 for an acre) of a seemingly unimportant bit of farmland. He had an epiphany that rising land value allows land owners to leech wealth from the community, leading to economic inefficiency and wealth disparities.

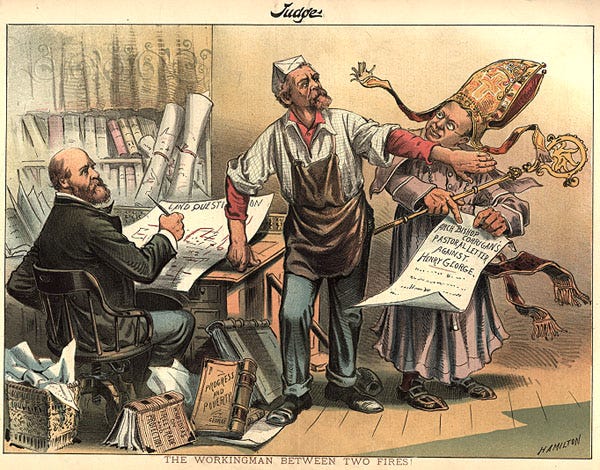

He thereafter wrote his magnum opus Progress and Poverty, which detailed an analysis of the economic properties of land and rent, and advocated for a land value tax. The book became one of the best selling books of the 1800s, and was for years the best selling book in the United States, second only to the bible. Henry George became a household name and even ran for mayor of New York City in 1886.

Since Henry George popularized it, a number of places[3][4] have implemented some form of land value tax. California’s Central Valley owes its massive productivity to the use of a land value tax to pay for dams and canals that irrigated the land. Japan reformed its land taxes in 1873 enacting a 3% tax on land value (quickly lowered to 2.5%) until the 1950s when taxation on buildings was added. The “Four Tigers” of Asia, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, also likely owe their economic “miracles” in large part to land tax reform. Places in all all 6 continents have used a land value tax for a time, and some places continue to. In the US, Pennsylvania and Delaware have had the most towns that use land value taxes. As of 2023, Pennsylvania has 17 towns that have a land value tax, in the form of split-rate taxation, where the land is taxed at a higher rate than buildings and improvements.

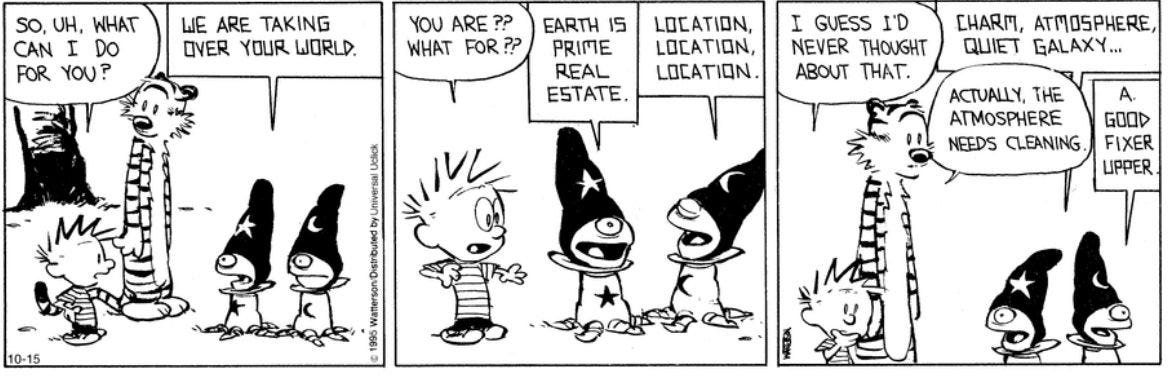

Monopoly and The Landlord’s Game

The classic game Monopoly was based on a game called The Landlord’s Game created by Elizabeth Magie, a follower of Henry George and resident of Georgist town Arden Delaware. The purpose was to teach people about the problems associated with land ownership and the need for the land value tax.

Players would play two phases. In the “Monopoly” phase, players pay rent to owners of land based on the land rent, improvements the owner has made to the land, and improvements adjacent owners have made to their land. There are land taxes, improvement taxes, and wealth taxes in this phase. Inevitably, wealth inequality between the players will accumulate. When one player gets rich enough, the rest of the players can choose to switch to “Prosperity” rules where the previous taxes are abolished, and land rent is paid as a tax, while rent from improvements is paid to the owner. The game then ends when the poorest player doubles their money.

Its really a shame that these elements weren’t kept in the Parker Brothers game of Monopoly.

Traditional arguments

While my conclusion is that the Land Value Tax is beneficial because it solves an externality, Henry George as well as modern Georgists often use other arguments to justify a Land Value Tax.

One of those arguments is a moral argument that land did not start owned by anyone and therefore shouldn’t be owned by anyone (or equivalently, owned by everyone). The idea is that something is owned by you only when you do work to improve it. Often the idea is also put forth that a severance tax should be paid to society by a person that takes natural resources in order to utilize them, and the land value tax is a kind of severance tax that pays society for the privilege of depriving others the use of it.

This argument is not very convincing to me. It isn’t very consistent either. If you take metal from the earth and fashion it into a shovel, why is it reasonable to own that shovel, but if you build a building on land, its not ok to own the land? The obvious reason is that land has the aforementioned externalities involved, and the extraction and use of natural resources does not.

One major problem with taxing the natural resources on the land is that doing so leads to a disincentive to safeguard those valuable land features, because they aren't actually valuable to the owner. All the value would be taken. If a property has a beautiful waterfall on their land, instead of being a valuable asset to the landlord, it would instead be a liability that costs them money every tax day. One could hardly blame the owner for not maintaining it or even destroying it in order to pay less taxes. But such a situation would of course be tragic. This is the importance of incentives: we do not want to disincentivize land owners from maintaining waterfalls, natural habitats, etc and we certainly do not want to incentivize land owners to destroy that natural value. This is why a land value tax should not tax the natural resources on the land itself, but only the externalities conferred from outside the property lines of the land. We want land owners to safeguard the natural value of the land. Everyone loses if people can’t reap the rewards of maintaining natural features of beauty and curiosity on land they own.

Another common argument given in favor of land value taxes is that taxing the land cannot reduce the supply of land, and therefore it is an ideal tax that does not distort the supply of land or incentives around land. However, this is misleading. This would imply that a government could tax the land as much as it wanted without consequence. This is of course not true. While the land will of course exist regardless of the tax, its utilization will change depending on the tax. Market distortions are caused when the land is taxed at anything other than 100%. If below 100% it allows land owners to collect [unearned] economic rent and results in the land being inefficiently underutilized. If taxed above 100%, unimproved land would be abandoned and land that does have improvements would become inefficiently *over* utilized.

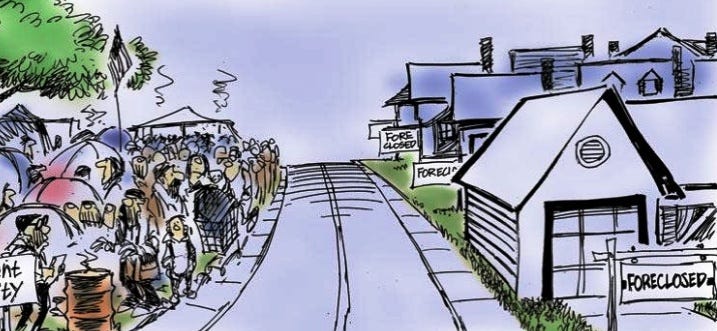

Solving the housing crisis

As I teased above, there are many incredible sounding benefits claimed about the Land Value Tax. One is that it could solve the housing crisis. How is that possible?

The answer is that it would reduce the cost of housing. There are a number of effects that all fundamentally lead to lower-cost housing:

A Land Value Tax would eliminate nearly all of a land owner’s ability to profit off the externalities conferred upon the land, and therefore the owner would have to utilize the land in order to pay off the cost of the land (both its purchase price and the land tax). Land owners could no longer make a profit by simply letting land sit empty. More land development would certainly mean more housing, and this additional supply would reduce the price of housing.

As the Land Value Tax replaces property tax, the additional disincentive to construct buildings and other improvements on the land would be eliminated. Property tax punishes improvements and rewards steady decline.[5] Eliminating property taxes means you would no longer be punished for investing in your neighborhood. One can build a house or complex without paying any additional tax. This will cause a further increase in land development, including housing.

As the Land Value Tax replaces other taxes, because it can’t be passed on to renters, renters would continue to pay rent as normal (likely decreasing because of the above two reasons), but would see their other tax burdens eliminated, giving them more expendable income. This might be some pressure to increase rents, but rents would not increase as much as the tax burden decreases. And its been found that most homeowners see their tax burden go down with a shift to Land Value Taxes.[5]

Longer term, because landlords would have an insignificant incentive to artificially inflate the value of their land by supporting policies that restrict housing construction, local politics would no longer be polluted by that kind of NIMBYism (although other kinds of NIMBYism may still exist). Over time, this would lead to less restrictive and healthier local building policies.

Implementing a land value tax should substantially increase the density of a city and basically “pull it inward” as the growth of urban sprawl slows or even reverses. Places that were above average value will become more dense and more valuable, and places that were below average value will become less dense and less valuable. This effect would make both urban and rural land more affordable. Cities would see cheap farm land much closer to its borders or even within its borders, and less farm land would be overtaken by urban sprawl.

Existing municipalities that have used a Land Value Tax have indeed seen substantial increased development. A study[2] of cities in Pennsylvania found that for every 1% shift off taxed building value and onto taxing land value there was a 16% increase in the value of construction permits issued. Towns like Harrisburg and Allentown had enormous growth after the implementation of Land Value Taxes in the 1980s and 1990s. Several towns near Melbourne Australia that taxed only the land experienced 30% higher growth than other towns in the area from 1974-1984. A 1997 study comparing Pittsburgh to 14 other Rust Belt cities found that Pittsburgh, which had a land value tax, saw a 70.4% increase in the value of building permits in the 1980s, while the comparison cities saw a 14% decrease in the same period.[5][6] Arden, Delaware has even spawned offshoot towns of Ardentown and Ardencroft.

The current regime of property taxes rewards land speculation and unused land. The property tax system and the lack of a land value tax results in the familiar sight of the odd vacant lot or run down parking lot surrounded by skyscrapers. Just look at this investment advice that emphasizes investing in medium-density housing and recommends not investing in or around central business districts. These perverse incentives drive people and companies to squander community resources by buying land and leaving it empty, building something ugly and cheap that won’t increase their tax liability, or buying distressed historical buildings and letting them decay and collapse. Switching from property tax to Land Value Tax fixes this in an economically efficient way. By contrast, laws against vacant homes or taxing them more is a blunt tool and distorts the market in negative ways.

A land value tax seems likely to be able to reduce housing costs, urban sprawl, gentrification, and homelessness too as a result. Even if there were no other benefits, this should motivate people to better understand the economics of land.

Reducing recessions by fixing the housing cycle

Let me take you back to the rip roaring days of 1997, when an economist named Fred Foldvary published a paper called The Business Cycle: A Georgist-Austrian Synthesis.[8] The paper outlined a hybrid economic theory that he used to predict a “depression” 11 years later in 2008. The theory is backed up by several centuries of data showing a shockingly regular 18 year housing cycle in a number of western countries that was disrupted for several decades by WWII.[9] The real estate cycle may have been a major factor in the great depression as well. Fred Foldvary’s British doppelganger Fred Harrison also predicted the 2008 financial collapse, in 1998 one year after Foldvary did. He even wrote a book about it in 2005 called Boom and Bust.

So why is there a business cycle for land? The reason is that land can’t be produced and substitutes are expensive and/or suppressed by red tape around land development. While supply and demand usually lead to more being produced as more is demanded, bringing the price back down, things with very inelastic supply like land simply see their market prices go up and up as people speculate on land value. The value of the land will increase past the point where it can be economically used. People can’t afford homes and have less disposable income, farms and businesses can’t afford property they need so can hire fewer employees, and the pyramid collapses. This ripples out to affect banks that have significantly devalued collateral on the books and no longer have many borrowers that can afford to buy homes and land, construction companies that no longer have clients, etc etc. This cycle is then exacerbated by government intervention that bails out failing banks and businesses, throwing more fuel on the fire so the next collapse is worse than it otherwise would have been.

Eliminating the ability for land owners to profit from community improvements would eliminate most of the positive feedback loop that causes the boom and bust cycle, making the cycle much slower or perhaps eliminating it for good. This of course doesn’t mean recessions would be completely eliminated, but it seems like it has a good chance to eliminate the ones caused by land speculation.

Before he died, Fred Foldvary predicted a depression in 2026 for the same reasons he predicted one in 2008, and Fred Harrison maintains a similar prediction.[12] 2026 is also 18 years after 2008. So watch out for yourself in the next couple years.

Reducing wealth inequality through land reform

I also claimed the Land Value Tax could narrow the wealth gap. While solving the housing crisis and reducing recessions goes a very long way towards doing this, the Land Value Tax also helps with the wealth gap by eliminating a source of wealth leakage for many people, allowing them more opportunity to rise up in the world, start businesses, and help their communities. People investing in their community see much of the value of that taken by land owners. With a Land Value Tax, this money instead returns to the community, lifting all boats. With the Land Value Tax, the benefits to the middle class and poor do not come from taking from the rich, but instead come from an alignment of incentives and a reinvestment of community value back into the community rather than leaking into land values.

Simplifying Taxes

Another benefit of the Land Value Tax is one it shares with property taxes: it can realistically replace other taxes in any municipality. Some places are commerce heavy and can’t rely on income taxes. Some places are purely residential and can’t rely on sales tax. However, all places have land that can be taxed. The more sales to be had in a place or the more residents living in a place, the more that land is worth and therefore the more tax it can sustain. Towns wouldn’t need to make decisions about what mix of sales tax and income tax makes sense, the economics work it out automatically. States and nations could even simply collect a fixed percentage of the taxes each local government collects, rather than taxing people directly. If truly done as a “Single Tax”, this could vastly simplify taxation.

So where’s my Land Value Tax?

But if land value tax is so great and was so popular in the 1700s and 1800s, and popular enough in 1900 to spawn one of the most recognizable board games in history, why isn’t it prevalent today?

I suspect the primary reason is the distraction and aftermath of WWI and WWII. People in 1700s and 1800s America didn’t like experiencing the growing poverty in wealthy and prosperous places, and were eager for change. However, after WWI and WWII, the US got wealthy enough that an enormous fraction of people escaped poverty and entered the middle class. And in Europe, inequality was greatly reduced (major wars tend to do that). Also cars became wildly popular worldwide and greatly expanded the area that was practically accessible to people. This effectively increased the supply of accessible land which pushed down prices and allowed people to live in cheaper areas farther from where they worked. All of these things combined to temporarily solve the poverty crisis[11] that began in the late 1800s, which is eerily similar to today’s housing crisis. This solution lasted a number of decades, gradually decaying as the US slowly lost its spot as practically the world’s sole manufacturing nation after WWII, as urban sprawl reached an equilibrium curtailed by traffic congestion and long commutes, and as a long peace again built up the wealth of nations and the deep poverty that Henry George found comes with it. We could solve this problem again by finding an even more convenient and long-range transportation method, like PRT, but ultimately this would also be a temporary fix.

Of course, there was also always push-back to the Land Value Tax by land owning interests who want to continue using land as a speculative asset that can capture economic rent (in addition to leaser rent). Those who benefit from rigging the game will generally try to keep the game rigged in their favor and have the resources to do so. And for some reason, there is a belief among some progressives that property tax is a regressive tax that puts a higher burden on lower-income taxpayers than on higher-income ones, however there is no strong evidence of this. Nevertheless, that perception has added to the push-back against property taxes and the Land Value Tax by similarity.

Implementing a Land Value Tax

I’ve concluded that the best way to implement a Land Value Tax is as a monthly payment on about 95% of the rental value of the land area a person owns, with the option to set up auto-pay. People would buy, sell, and use land as usual, but would simply pay a rent to the government for the privilege of having full control of it. See note [13] for justifications.

The enactment of this tax would coincide with elimination of property taxes, sales taxes, and reduction of income tax and other taxes (excepting other Pigouvian taxes) as much as possible. Enactment of a Land Value Tax should not mean that the government collects more taxes, only that where the necessary tax revenue comes from changes.

It is often said that a problem with the Land Value Tax is that its difficult to assess the land’s value. However, it is clear that it is no more difficult than assessing property value, which is almost a ubiquitous practice. In fact, assessing land value should be substantially easier than assessing property value, since the vast majority of the value per acre of one plot is identical to the value per acre of the plot next to it. Assessment can happen yearly on the level of a neighborhood, and specific adjustments can be made for plots with above average value for their block eg a particularly nice view, or special property rights (eg higher height limits).

One issue that might come up is: what do you do to prevent grandma from losing her home to increasing taxes? Without any consideration, if she didn’t have enough money to pay the land tax, she might have to sell and downsize. But another solution is to get a mortgage to pay the taxes, which should provide plenty of value to live off as well.

An example: Let's say this grandma had a $300,000 property and the rental value of the land was $30,000/year ($2500/month). If the value of her land doubles so next year she has to pay double the tax. If she can still afford to pay the original tax, but not the new tax, she would have to borrow $30k each year.

If she takes out a loan at 4% interest, she would still be above water for 8 years before the amount she owes on the loan exceeds the extra value her land got (not including its original value). And she would have a full 15 years before her land would have to be sold to cover the loan. Certainly long enough to make arrangements to move if necessary.

If instead of a single one-time land value increase, her land increased at a steady rate, she could potentially sustain such a loan forever. For example, if the loan rate was 4% and the land increased in value at a rate of 4%, the value of the land would increase faster than the loan liability would (because the loan principal would always be lower than the value of the land). If instead the land increased in value at 3% and the loan was still at a 4% interest rate, your grandma could remain above water for literally over 250 years before you would have to liquidate the loan.

So as long as you can get a loan using your illiquid wealth as collateral, it seems to be quite reasonable to simply obtain a loan for the payment of taxes with no real hardship. However, if even this is not sufficient for some reason, it might be reasonable for a municipality to allow her to defer taxes and accept payment once the house is sold. This could give an owner several years to plan a move or could even defer until death of the owner.

Simply enacting Land Value Taxes as described above in a place that doesn’t use them already would be a devastating surprise to anyone who holds land. Surprises like that not only place people into hardship, but also cause economic inefficiencies of their own as economic plans are dashed and wasted. So it would be prudent to slowly introduce a Land Value Tax over perhaps a decade or two. Start with a low land value tax that replaces some property taxes – a split rate tax system. And every year increase the land value taxes, and correspondingly reduce some other tax to compensate. This would slowly switch things over so people could still take advantage of their land as planned for a while, but would eventually have to shift their financial strategy to something more productive for society. Grandfathering many properties into older taxes is not recommended. California’s experience with their 1978 Proposition 13 that locked in property taxes at 1976 values has resulted in erosion of the tax base, dependence on state aid, inequality and tax unfairness, and reduction in available housing.[7]

What to do with the money

Generally speaking, what is done with tax revenue is somewhat irrelevant to consideration of how to tax. Whether something good or bad is done with the proceeds, it is clear that the Land Value Tax is an all around better tax than common alternatives. But if a community ramps up to eventually taxing at the somewhat optimal rate of 95%, what if this is more tax revenue than the town’s government needs?

One practical possibility would be to use some of the proceeds of the tax to pay back residents for other taxes they’re required to pay by higher levels of government. Eg each person in town could receive back any income tax they paid up to a certain amount, plus perhaps 20% of any income tax paid above that amount. Any state sales tax could be forgiven in this way as well. Doing this would correct some or all of the deadweight losses caused by those taxes, depending on how fully those taxes are repaid.

Another alternative use would be to attempt to distribute the excess tax revenue to the citizens in the community that produced the positive externalities that the Pigouvian (or Tidroudian) land value tax is correcting for. This could take the form of garden contests with cash prizes, a positive externality voucher each individual could decide how to allocate, some kind of externality assessment committee, etc.

A 3rd possibility is a distance-based citizen’s dividend. One might do this, for example, by earmarking 1/3 of the excess taxes collected from a parcel of land to owners of land on their block, 1/3 to other owners of land within 1500 feet of their land, and the last 1/3 to all other land owners in town. The idea being that the closer neighboring land is, the greater that neighboring land effects a given plot with its positive externalities.[14] Also, it would mean that when deciding to build something that will have positive externalities for the community, some of the cost of building it will be recouped via higher taxes received by the builder, which would lead to a higher (and more economically efficient) amount of positive externality producing activity happening in town.

Its important to note that this would inevitably be somewhat inaccurate, in that the producer of a positive externality would only be partially rewarded. But a major benefit is that this mechanism provides a partial correction for all positive externalities for many things where the producer could not be accurately rewarded or even identified, including situations where the externality remains unknown. This could be an interesting mechanism paired with a Land Value Tax to correct for both sides of positive externalities even for externalities that could never be feasibly individually identified.

Conclusion

Milton Friedman called it “the least bad tax”, but as I’ve explained, the land value tax is not only “least bad” but actually a good that increases economic efficiency through its collection. There’s a lot of evidence that places that have used the land value tax have become wealthier and better off for its use. However, nowhere has implemented the Land Value Tax in its truest form: where near 100% of the externality value is taxed.

Existing towns should consider enacting split-rate taxation that gradually reduces taxation on buildings and improvements and gradually increases taxation on the land itself. The Land Value Tax seems like a credible and believable way to substantially increase economic efficiency and reinvigorate our towns and communities.

Footnotes and additional references

However, the number of hides a region was taxed based on were often based not on any kind of land surveying but based on loose assumptions of the productive capacity of the area that were sometimes suspiciously convenient for the taxing authority. The related Heregeld tax in England was hated because it was an extra hefty tax levied by the King Cnut alongside the Danegeld tax and Cnut was excessively strict about it, giving people only a 4 day grace period to pay. If they were later on payment than that, their land could be entirely confiscated. The Danegeld was also hated for similar reasons of being too high as well as bitterness around the many exceptions given out to a favored few.

The Impact of Two-rate Taxes on Construction in Pennsylvania by Florenz Plassman (advised by T. Nicolaus Tideman). See the conclusion in chapter 8.

https://www.progress.org/articles/where-a-tax-reform-has-worked

https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/successfull-examples-of-land-value-tax-reforms/2011/02/05

The Impact of Urban Land Taxaction: The Pittsburgh Experience by Wallace E. Oates and Robert M. Schwab

See also: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1103584

There are those who say the 18-year housing cycle is a myth, like John Lindeman, however he seems to not understand how big of an impact WWII had on the world (and his analysis only goes back 120 years vs others that go back twice that long).

Should things like a beach water front or a stream running through your property count as an externality? That gets tricky, but luckily there’s a whole legal discipline around water and air rights to fall back on there.

While people below the poverty line has overall decreased over time since the 1800s, there was a rise between 1850 and 1870. Not only that, but even when the proportion of people in poverty began decreasing again in the late 1800s, most people in poverty were still getting poorer, which was related to the quickly rising income inequality between the 1870s and WWII.

Although Foldvary did muse that Covid might have disrupted the cycle, I don’t buy it given that past pandemics like the Spanish Flu didn’t disrupt the cycle, nor even did WWI disrupt it in Europe. Only WWII managed to disrupt the cycle.

Doing it this way would have a number of advantages. Paying monthly means smaller payments and eliminates the problems caused by people forgetting to plan for large lump-sum taxes each year. Having an auto-pay option allows it to be as automatic as payroll taxes. Both of these things would reduce how painful the tax feels and would place it on a level playing field with other taxes, popularity-wise.

Charging 95% of the land value ensures a 5% buffer so its very unlikely the tax would exceed the value of the land, since that would cause people to abandon raw land they own. Taxing based on rental value as opposed to a percentage of the purchase value is more accurate, since it is not clear how to choose an appropriate percentage without taking into account the rental value.

Taxing on regular basis is beneficial vs taxing only on the sale of a property because it ensures a more predictable tax on the owner and more predictable revenues for the government. Also, while taxing the land-rent would theoretically be equivalent to taxing the land value on land sale, regular payments would not create a perverse incentive to simply never sell their land like a tax on land sale would. And the tax should be based on land area vs assessed land value to both make the tax simpler to administer and to make the tax only on externalities and not on value that exists on the property itself.For larger plots, there might be some substantial effect where the developments on one part of the plot increase the value of adjacent land on the same plot (with the same owner). It might be reasonable to say that plots of a certain size are split into pseudo sub-plots when distributing a citizen’s dividend style reward, such that the owner of a large plot might pay some of their land value tax back to themself on the basis of one sub-plot they own conferring a positive externality onto another sub-plot they own. But this effect is very likely to be small for plots that are less than a few acres large.