Taxes

A mine field worth understanding

As inevitable as death. Possibly more painful. Everyone’s familiar with taxes as the way governments pay for what they do. In this post, I want to summarize how the collection of different types of taxes affects the economy.

Taxes are any wealth confiscated from people for government use that isn't a direct government service provided and voluntarily opted into. By this definition you have many usual suspects, income tax, sales tax, etc, but you also have other odd things that fall into the category, like parking tickets and civil forfeiture.

A little history of taxation

The first instances of writing and proto-writing seem to have been primarily of an accounting nature having to do with tax collecting or money. The Rosetta Stone, which allowed historians to translate hieroglyphics, consisted mostly of tax law. Taxes have been a very important enabler of power surely long before writing existed.

The first recorded taxes date back to around 6000 BCE in modern day Iraq where a fraction of all goods were periodically taken as tax and recorded on clay tablets. Normally taxation was quite low, but in a crisis or war, taxes could be as much as 10% of the assessed goods. The collection of temporary taxes or temporarily high taxes to finance war has been very common throughout history.

Ancient Egypt circa 5000 BCE similarly taxed goods as well as land, then tithes and corvée labor became common the mid 2000s BCE. The most common taxes throughout history were on land and the production of land. Tithes were a fraction of harvest paid to the government, and corvée was mandatory unpaid labor done in service of the government, usually for those who could not pay a tithe. As early as 3100 BCE, Egyptian kings would ride around the countryside each year during an event called the Cattle Count of Shemsu Hor account for farmers crops, produce, and of course cattle. Corvée labor built the pyramids and was used in Egypt all the way until the end of the 1800s CE! Ancient Egypt also introduced an occasional wealth tax to pay for wars.

It may come as no surprise that Ancient Rome introduced a number of novel taxes, sales tax, income tax, inheritance tax, and also may have been the first to use import tariffs. While sales tax has been historically and remains today a difficult tax to enforce, the Roman Empire only instituted it on goods sold at public auction, making it tractable.

State resource or product monopolies can be considered to have a sales tax component to it, as a monopoly allows charging higher prices that would be possible in a market of free competition. This has been a common way for governments to make money throughout history, being used in the Ancient Egypt as early as the mid 2000s BCE. The Ancient areas of China, Mesopotamia, and Greece began monopolizing resources as a common practice between 1100 and 100 BCE, among I’m sure many others. Salt was a common resource monopolized in this way, as its necessary for life and far more scarce and valuable in the ancient world. Monopolies on useful or precious metals like bronze, iron, silver, and gold were also common.

Over time, modern taxes have shifted to various taxes on transactions, like income tax and sales tax. Taxation on real estate remains a very common tax. Modern tax systems have also gotten substantially more complex.

A labyrinth of taxes

I’m going to break down the types of taxes into 4 loose categories: Taxes on transactions, taxes on assets, taxes on behavior, taxes on people, and taxation via money. There are a few odd ones that could fit in multiple categories, but the categories helps group taxes with some similar properties and effects.

Taxes on transactions

The type of taxes almost everyone is familiar with today are taxes on transactions. All of the following are taxes of this kind:

Sales taxes

Value added tax and turnover tax

Excise taxes

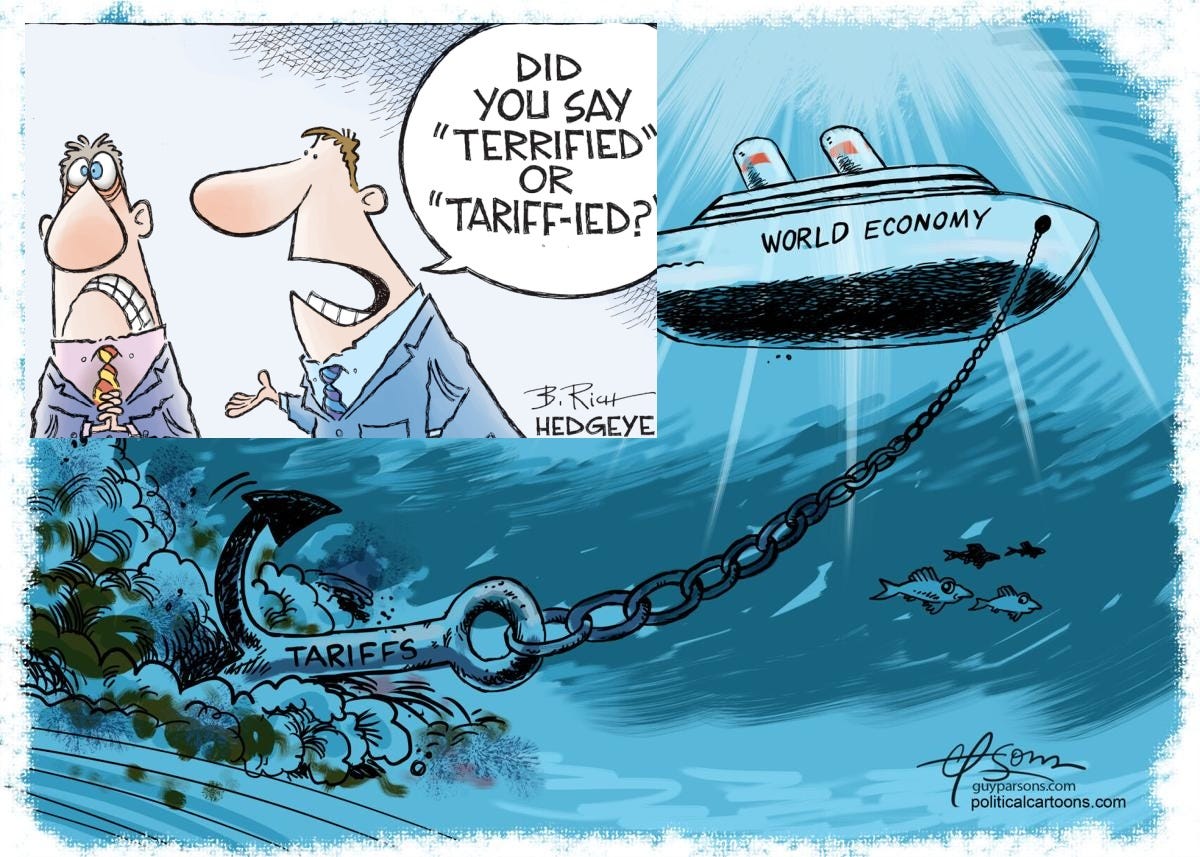

Tariffs

Income tax and business taxes

Capital gains tax

These kinds of taxes have historically been difficult to collect because it’s hard to keep track of individual sellers and transactions. Even today, there is substantial sales tax evasion of around 15-20%, which is around the same evasion rate for income taxes.

Value added taxes (VAT) and turnover taxes are like sales tax, but a transaction is not taxed on the gross amount of the sale but rather on the mark up above the amount its components were bought for.

Excise taxes are basically sales taxes on certain products. Excise taxes are generally levied either to discourage the purchase of a particular item or to pay for related government services. “Sin taxes” on things like alcohol, tobacco, or sugar aim to reduce the usage of those items either with the usual justification that reducing their usage is good for people or society. Luxury taxes similarly have been levied in an attempt to incentivize people to put their money to more productive use as well as intending to tax the rich more. Taxes on airplane tickets are there to pay for government airport services. Similarly, gasoline taxes pay for roads but also have an aspect of paying for the externality of pollution as well (which makes the tax Pigouvian, elaborated on further down). The Ramsey Rule suggests that the optimal way of implementing sales taxes would be to tax each product based on its elasticity, such that the deadweight losses for each product are the same, which presumably minimizes the deadweight losses. This of course assumes the government would accurately estimate the elasticity of various products, a very difficult thing to do.

Sales taxes (and the similar VAT and turnover taxes) are generally considered regressive, they put a greater burden on less wealthy folks vs the more wealthy, because the wealthy generally spend a smaller fraction of their income on items that sales tax is charged on and spend more money on things, like real estate.

By contrast, income tax is often implemented in a “graduated” fashion using tax brackets that takes a higher fraction of income from higher-income folks using tax brackets which is intended to make them progressive. However at least in the US, the enormously complicated system of rules and loopholes means that income taxes are actually regressive instead of progressive, despite the use of tax brackets, and has become more regressive over time. A number of US states have a flat income tax where everyone is taxed the same percentage regardless of their level of income, which is also regressive.

And business taxes are usually implemented as flat taxes since the reasons for a graduated tax system seemingly don’t apply to businesses like they do for personal income (namely that people have substantial cost-of-living expenses businesses don’t have an equivalent for). However, in reality the stock holders of the business bear those taxes, and so a flat business tax works effectively like a flat income tax on business owners.

Sales tax incentivizes vertical integration so as to avoid repeat taxes when selling components from one company to another, and value added tax is touted as better because it does not do this to the same degree. However the administrative costs of value added taxes are higher, one estimate being 4% of the amount raised.

Similarly to VAT, capital gains taxes only the gains, rather than the gross amount sold. However, there are still distortions with capital gains, since it incentivizes people to find ways to avoid selling capital. For example, if one wants to sell stock in company A to buy stock in company B, a more tax advantaged option would be to convince company A to instead buy company B. No sale of stock, no capital gains needs be paid. That can be a powerful incentive to merge companies that otherwise have no business merging.

Tariffs are a tax on imported goods. This tax is collected once when entering the country, so it skirts the line between a transaction tax and an asset tax. It has results similar to a sales tax. The salient difference is that it further disincentivizes foreign goods and so is basically a protectionist sales tax. It distorts the market more than sales tax does because of the way it arbitrarily disincentivizes foreign trade. Many think that tariffs should be completely eliminated, however they’re hard to get rid of because of regulatory capture – heavy lobbying from the domestic special interests benefiting from the tariffs keeps them in place. Domestic companies selling products benefit by having less competition at the expensive domestic buyers who lose by having to pay higher prices, as well as of course the foreign companies that lose the business.

Taxes on assets

Taxes on assets have been common throughout history because its easier to assess someone’s assets periodically than to keep track of every transaction. In this category, we have:

Property tax

Land value tax

Wealth taxes

Inheritance tax and estate tax

You’re probably familiar with property tax, which taxes real estate including the land and buildings on the land. Land value tax, by contrast, taxes the land but not buildings or improvements on the land. And wealth tax is an all encompassing tax on your entire net worth.

Historically, at times a wealth tax consisted of a tax collector coming to your property and counting up the value of all your assets. These days, people’s assets are far less physical and more disperse, so its gotten more difficult to assess wealth taxes. Several countries collect wealth taxes. For example, Switzerland has done this since 1840. A few countries have enacted wealth taxes in the past few years, and others have discussed it, seemingly in an attempt to ease economic inequality. However, wealth taxes can also lead to capital flight as wealthy people move out of a country to avoid high taxes.

Property tax disincentivizes developing and improving land, since doing so increases the taxes owed. By contrast, a land value tax that taxes just the land and not improvements does not have this effect. Land value tax is one of the only taxes that can’t easily be passed on to someone else. An increase in land value taxes won’t increase the rent the owner can charge tenants because the fixed supply of land leads to the price being entirely demand-driven. Conversely, property taxes are difficult to pass on in the short run because landlords usually have no control over the supply of real estate, but eventually because increased property taxes disincentivize development, an increase will eventually lead to passing on some of the tax to renters in the form of higher rent.

Inheritance and estate taxes are kind of a combination of a tax on assets and a transaction tax. The transaction is inheritance of assets after the death of the owner. The wealth taxed is the wealth they had when they were alive. While it seems like this kind of tax shouldn’t have any deadweight losses, it generally incentivizes people to transfer their assets over time to their future heirs in potentially complicated and messy ways, like in trusts and tax shelters. The high values involved also incentivizes higher than normal tax evasion, as does the fact that the effective rate of the tax can often differ wildly for the same amount of wealth being taxed depending on how the tax law is written.

Taxes on behavior

This last category of tax has taxes on peoples’ behavior. These are often taxes designed to discourage certain behavior, potentially to correct for a negative externality. Examples include:

Cap and trade

Carbon taxes

Gambling taxes

Bank taxes

Fines

These are all meant to discourage some activity considered costly to either society as a whole, or the individual. Gambling taxes are intended to discourage gambling for the benefit of the individual while bank taxes on at-risk capital are intended to discourage banks from taking exorbitant risks, for the benefit of the banks customers (and potentially the tax payer who might be compelled to bail them out when things go wrong).

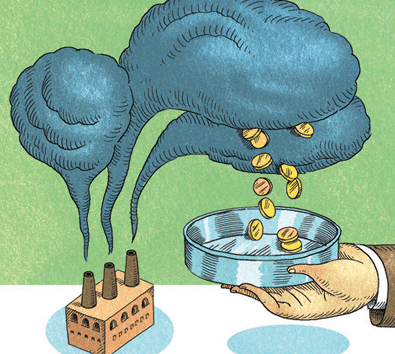

Carbon taxes or emissions taxes are a fee charged for emitting a certain amount of emissions, which disincentivizes carbon emissions and potentially helps correct for any negative externality the emissions cause. Cap and trade may also have a taxation component where licenses to emit pollutants can be sold to companies. This is similar to an emissions tax in that the polluters are charged for emitting pollutants, however cap and trade is economically an inferior mechanism that is less likely to lead to economic efficiency. Sometimes polluting companies are even granted these valuable licenses, which end up being a subsidy for them instead of a tax.

Fun fact, an Exxon mobile was caught on camera talking about how they support carbon taxes publicaly only because a “carbon tax isn’t gonna happen”.

If the tax exists to correct for a negative externality, they’re known as Pigouvian taxes. An emissions tax is one example of this. I’ll talk more about those in the next section.

Our complicated system of tax deductions also basically is a set of taxes and subsidies to behavior. Married couples get tax benefits in most cases. Homeowners and charity contributors do as well. These effectively mean that some behavior is taxed more than other behavior.

Fines are interesting in that they’re not usually talked about as taxes, but functionally are similar to the rest here. Often times the intended purpose of a fine is punitive, but another functional purpose is a means to fund the government. For example in in 2012, San Francisco parking tickets generated about double the revenue that the parking meters themselves generate. This leads to a perverse incentive to make parking legally more difficult, like posting short time limits on parking and making parking signage confusing. Civil forfeiture falls into this category. Its uniquely unjust legacy is made worse by knowing that police basically use these seizures as another way to fund the department.

Note that excise taxes on things like cigarettes often have the intention of taxing the behavior of using those products (eg smoking for cigarettes), but I included them in a different category because the tax happens on sale.

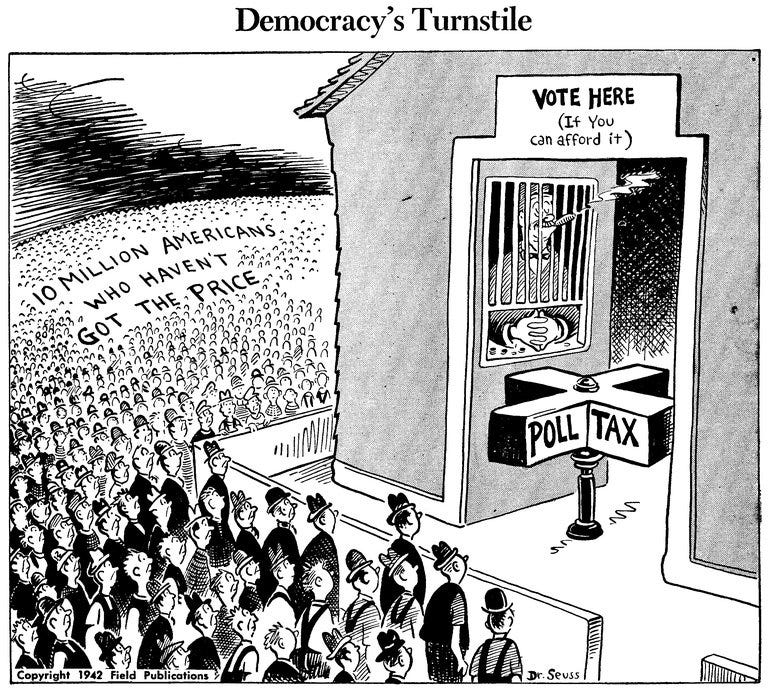

Taxes on people: The poll tax

This category has just one tax: the poll tax, a fixed tax per person. While this tax was used in many places in history from ancient times, it looks like there are no places that use it today. In the US, the constitution expressly forbids the federal government from collecting such a tax. However, several US states required collection of a poll tax to be eligible to vote as a way of excluding poorer folks, especially black folks, until the passing of the 24th amendment in 1964 prohibited it. There have even been a number of attempts to create “bachelor taxes”, which have also been very poorly received.

Poll taxes are considered very regressive and as a result have often been quite unpopular, so much so that they have sparked many a tax revolt throughout history. The effect of a tax like this would be to generally transfer wealth from the poor to the wealthy and politically connected.

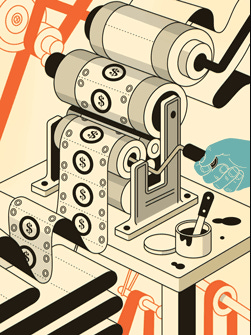

Taxation via money: Seigniorage

While often not considered a tax, the manipulation of currency has been used as a way to extract wealth from the masses since coins were invented in the 600s BCE, possibly as early as the use of metal moneys in the 3000s BCE. Seigniorage from minting coins and coin debasement were widespread in Ancient Greece. When a mint creates new coins, those coins are worth more when first used than they are later when the market has become aware of the increased supply of coins, and this difference is called seigniorage. When coins are debased, it decreases the costs to create new coins, which increases profit margins for the mint.

In modern times, fiat currency that can’t be debased (because there is no base) is used, but seigniorage can still be extracted. When banks create money, they’re extracting seigniorage from not only people who have money, but also people who are owed money denominated in that currency. For banks, these are somewhat opposing forces since creating money gives them seigniorage from the use of the money, but reduces the value of the mortgage contracts and other bonds they own. However, for a government that has substantial debt and also receives revenue from the printing of money (as the US does from the Federal Reserve’s “profits”), it gains from both kinds of seigniorage.

Seigniorage is generally a regressive tax on the people, since poorer people are more likely to hold a higher fraction of their wealth in money or debt. This kind of tax can be avoided by declining to buy fixed-denomination bonds (inflation adjusted bonds correct for this a bit), but because someone will be holding onto that money, the tax can’t be entirely avoided. Because its an indirect tax, most people aren’t even aware that this is something that is transfers their wealth to the government (and banks).

And this is one of the most insidious things about seigniorage. Unlike all of the other tax where someone is clearly paying for it, there is no receipt for how inflation affects you. Because of this and because of the complexities and indirection involved in how central banks manipulate money, its hard for the public to understand when this effective tax goes up and when they should be concerned about it. We most certainly should be concerned about it now. We should have been concerned about it in the 1970s.

The seigniorage caused by monetary inflation disincentivizes people from holding cash, and thus incentivizes people to find some other store of value, like stocks or bonds. And while the seigniorage doesn’t directly affect loans, the way that modern banks create money for a loan substantially increases the availability of loans. A bank today can usually create loans without any substantial bound other than the demand for loans. Because of this, while seigniorage puts pressure to increase interest rates, the easy ability to create money for loans pushes it back down.

There’s a lot more to say about this, and I’ll do a much deeper analysis of money, inflation, and seigniorage in a later article.

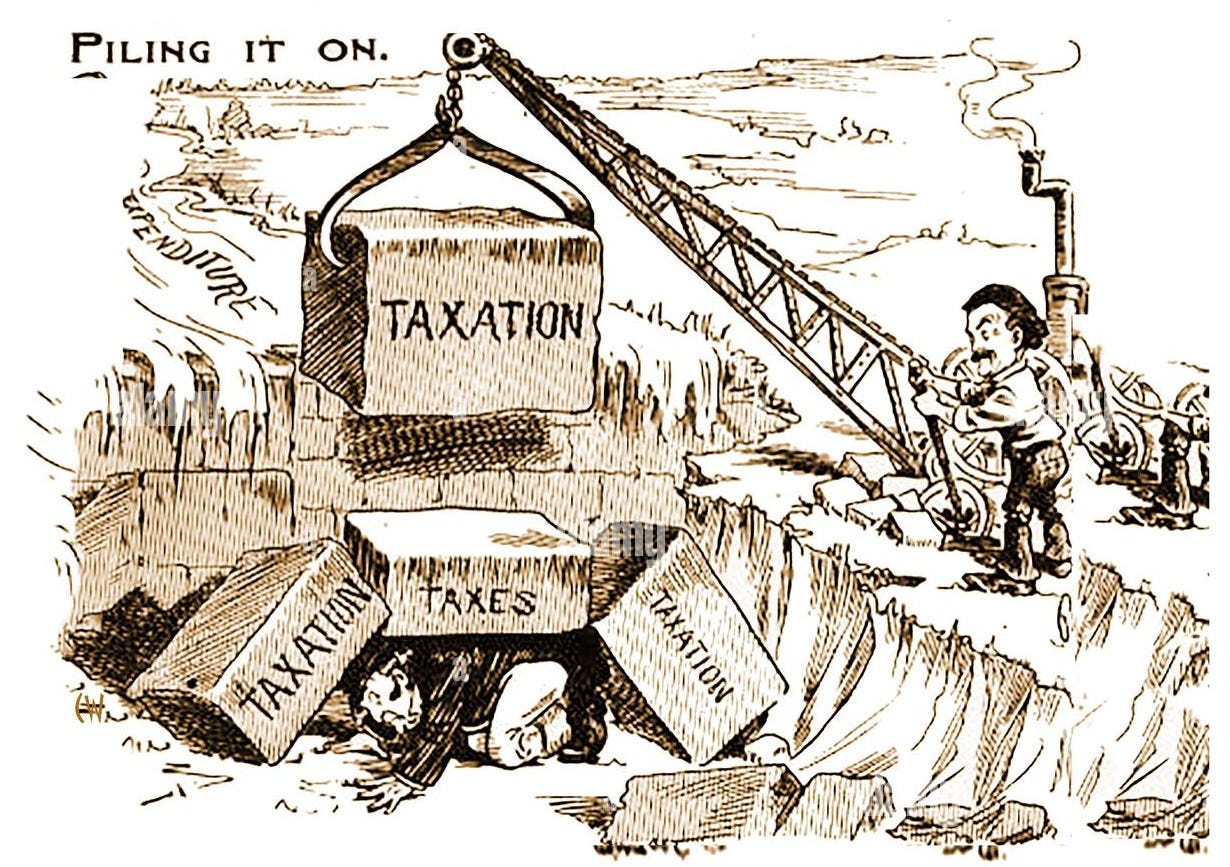

Deadweight losses

As mentioned above, taxes generally cause economic inefficiencies known as deadweight losses. A deadweight loss is an economic opportunity-cost that occurs when supply and demand can’t reach their optimal equilibrium.

If you put a tax on sugar, that means that some sugar production that was profitable without the tax is now unprofitable and therefore less sugar will be produced for any given market price. The supply curve shifts up. Because less sugar is produced, the price goes up and less sugar is sold. Since every trade results in higher economic utility for both the buyer and seller, the reduction in these trades means that those buyers and sellers who could not make a profitable trade because of the tax were robbed of that economic utility.

The reduction in transactions profitable to both parties is part of the deadweight loss. Market distortion that changes people’s behavior also causes deadweight losses by incentivizing people to do suboptimal things.

Taxing sales means fewer sales and inefficient vertical mergers. Taxing income leads to less people seeking work and seeking compensation other than direct income. Although the elasticity of job seeking is low (ie most people will seek work regardless of available wages), people will also attempt to find ways to avoid income tax, like employee health benefits and retirement funds that aren’t taxed or are tax deferred. Business taxes are passed on in the form of lower wages for workers and smaller budgets for R&D.

Taxes on behavior that aren’t Pigouvian also cause deadweight losses. Taxes on assets are generally cause deadweight losses slower or in less obvious ways, except for land value tax which actually reduces deadweight losses rather than creating them (because its essentially Pigouvian). Even monetary inflation causes deadweight loss in the form of price inflation, which has a similar effect as sales tax. The only tax that shouldn’t cause a deadweight loss is the hated poll tax, since like land value tax, the number of people is not dependent on the tax.

It has been estimated that the deadweight loss of taxes is something on the order of 30% of taxes collected, which would be $1.2 trillion for the US in 2021 for example, or $3600 per person. This is the same percentage of deadweight loss estimated for income tax as well.

Now, if the use of those taxes is beneficial enough, it could presumably compensate for those deadweight losses as well as the additional opportunity-costs taken from the tax payer. However, the existence of both of these costs means that in order for a tax to break even economically, the government activity funded with those taxes must be *more* efficient than whatever the tax payer would have done with that money.

Pigouvian taxes: The only good taxes

So taxes generally cause deadweight losses, however this can also work in reverse. Taxing just the right things in the right way can actually *reduce* existing deadweight losses.

Like most taxes, externalities also result in deadweight losses. For example, when a polluter pollutes, they are forcing the people around them to incur a cost rather than incurring that cost themselves. This means the polluter incurs a lower cost than the full cost, resulting in incentives to over-produce the activity causing the pollution.

It is well understood that the two most efficient economic mechanisms to deal with externalities (when property rights are already well defined) are either Coasian bargaining or a Pigouvian tax.

If you’re polluting my air and I have a right for my air not to be polluted, I can make a Coasian bargain with you where you agree to pay me a certain amount of money for a certain amount of pollution. Then the polluter is paying the cost to you, solving that externality. Interestingly, the problem can be potentially solved in the opposite direction, where you instead offer to pay me to move away from you. If paying you to move away is cheaper than paying you to pollute your air, that is a more efficient solution.

The problem with Coasian bargaining is that there are many cases of externalities where transaction costs are too high for such bargains to actually take place. Driving your car in a city releases exhaust that affects many thousands of people just a little bit, and every person in that city has their air polluted just a little bit by many thousands of drivers. Bargaining with every combination of those people would not be worth the effort for anyone.

In such cases where the transaction costs are not low enough (often because the number of players involved is high enough and the damage caused low enough), the most efficient known mechanism to correct the externality is to tax the polluter an amount equal to the cost they're incurring on others. This is called a Pigouvian tax, which "internalizes" the externality, counterbalancing it such that the producers are no longer incentivized to produce more polluting activity than is efficient for the market.

By the way, don’t listen to sources that incorrectly say things like sugar taxes or cigarette taxes are Pigouvian – those aren’t solving an externality and so aren’t Pigouvian.

Because a properly done Pigouvian tax reduces deadweight losses instead of causing them, the economics can be positive even when the activity the tax funds is *less* efficient than what the tax payer would have done with the money. In other words a Pigouvian tax itself is a productive service for the economy, unlike other kinds of taxes. This of course isn't an excuse to use taxes inefficiently, it just highlights that Pigouvian taxes are more efficient.

Making cents of taxes

Taxes have a number of attributes and effects:

Progressiveness vs regressiveness

Ease of tax evasion (not paying) and avoidance (switching to different activity)

Administrative costs

Indirect vs direct taxes

Some taxes are progressive, meaning that they put a heavier burden on the rich than the poor. Regressive taxes are the opposite. All the taxes I’ve talked about above are regressive except income tax, inheritance and estate taxes, and possibly land value tax. Some are more regressive than others, for example a poll tax is possibly the most regressive tax, sales tax is quite regressive, and property tax is only a little regressive.

Of the progressive taxes, income tax, inheritance tax, and estate tax are all progressive only because they’re explicitly designed to tax the rich more. Inheritance and estate tax are generally built to only tax wealth above a relatively high amount, eg wealth above $1 million in several US states. Note that a flat inheritance tax would still be considered regressive, not neutral, because of the somewhat fixed cost-of-living floor that doesn’t vary too much from human to human. Capital gains tax is progressive because the wealthy store most of their wealth in the form of capital. Land value tax is generally considered progressive, but it may be a somewhat neutral tax, since it seems that progressiveness or regressiveness of it depends on area.

Any of the taxes on transactions and behavior are easiest to evade, because keeping track of it all is difficult. Taxes on assets and poll taxes are difficult to evade, and monetary inflation is impossible to evade.

Avoidance is a different story. Tax avoidance is generally caused by a change in market incentives caused by a tax. Taxes on behavior intentionally cause incentive changes (away from the taxed behavior). Taxes on assets are generally the least avoidable, but can be avoided by moving out of the country (or relevant tax jurisdiction). Property tax is actively avoided by developing property less to avoid higher taxes that would be caused by additional buildings or improvements. Land value tax can’t be avoided at all because someone will always own the land. Neither can a poll tax, since you can’t stop being a person just to spite the tax collector.

Avoidance of transaction taxes generally cause undesired inefficiencies. Sales tax, VAT, and similar reduce sales. Sales tax also incentivizes vertical mergers. Income tax dampens the incentive to work a paying job and incentivizes more complex alternative kinds of compensation (like company health benefits).

Avoidance of the tax of inflation and seigniorage leads to most people putting their money into various investments like stocks and bonds. Unfortunately, most people aren’t financially literate and they aren’t likely to understand the quality of various investments and risks associated with them. This is why diversified stock index funds are so popular. Its also one reason so many people lose so much money when the economy crashes. Also, it makes currency a hot potato where investing in something that doesn’t beat inflation is still worthwhile over keeping money in cash. This incentivizes an inefficiently high amount of investment in lower-quality ventures. This likely has enormously harmful effects on the economy. Again, I’ll expand on this in a future post.

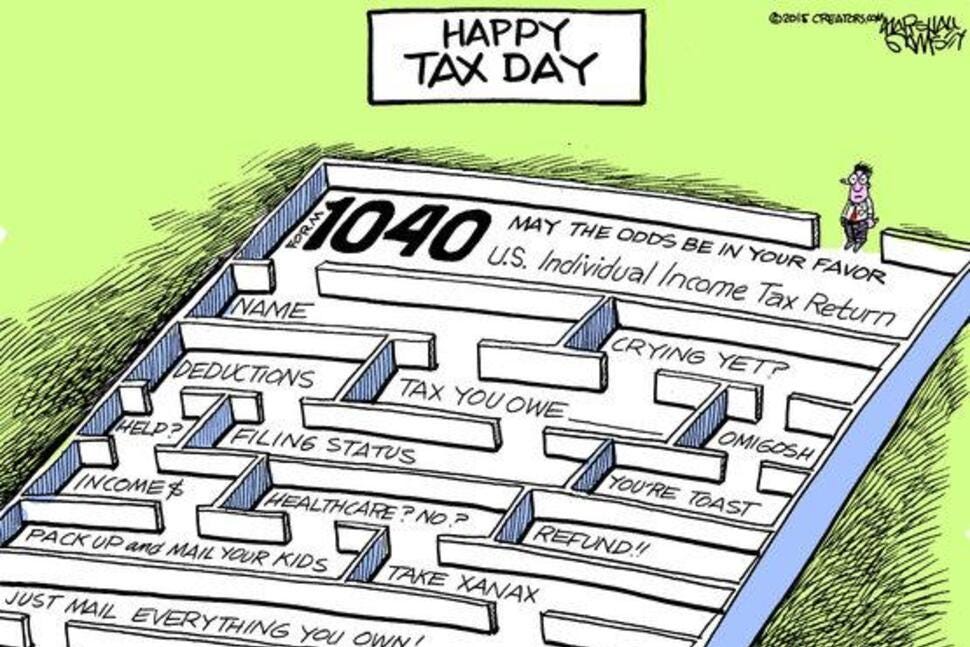

All taxes have administrative costs, but taxes on transactions and behavior have the most. However, the complexities of many modern tax systems by far and away dwarfs the administration costs of any type of tax. In the US, the IRS spends about $15 billion/year administering taxes, however the taxpayers themselves bear a cost of around $400 billion/year. A labyrinth of taxes means more headaches and costs for everyone.

Different taxes feel different types of painful. Income taxes are particularly painful because of the paperwork and time involved. But tax with holding, as annoying as it is, makes the collection of the tax easier, more consistent, and more or less a painless automatic part of most people’s paychecks. Sales tax and similar types of taxes are bundled into the price paid at the point of sale. By contrast, property taxes are generally paid yearly as a single large payment. This makes them generally less popular than other taxes that are more automatic.

A direct tax is a tax paid directly by the person who pays the tax. These are taxes on a person or business, their property, or their income rather than on transactions. Note that the IRS and several others define this slightly incorrectly, and the US constitution has yet another alternate definition. The concept of “direct” vs “indirect” taxes is a bit out dated and not that useful.

Taxes on transactions and behavior are indirect taxes, while taxes on assets and poll taxes are direct taxes. Seigniorage doesn’t really fall into either category, but if it did, it would be an indirect tax. Things like sales tax and VAT will usually be passed on mostly to the other party in the transaction, and some businesses will go out of business because the higher price leads to a lower quantity demanded. In a more monopolistic situation, the buyer bears part of the burden of the tax by paying a higher price, and the business pays part of the burden by selling a lower volume at a potentially lower profit margin.

Its traditionally stated that income tax and taxes on business profit can’t be passed on to anyone else, but the reality is that some of the burden of income tax does fall on employers and similarly some of the burden of business taxes falls on customers, as employees and/or employers leave the country/area over time. Land value tax is also said to not be possible to pass on to renters, however again, this is only true over short time spans. Over decades, supply of a given quality of land can be increased with additional development in the area (eg better transportation connections) or decrease by stagnated development. Property tax can be partially passed on for similar reasons as well as because supply of the kind of property (eg housing) can be increased by development within 5-7 years.

Regulations: Hidden taxes

Keep in mind that taxes are not the only thing government enforces that distorts the market and extracts value from people. Regulations that require businesses to do certain activity is quite similar to a tax. For example, anti-money-laundering (AML) regulations effectively turn banks and other financial institutions into a big brother style arm of government surveillance. It costs these business quite a lot to provide this service to the government in the form of personnel time and a lower value service to their customers, all this for a regulatory system many considered to be one of the least effective policies in the US. Similarly, requiring businesses to pay for medical insurance for their employees is also effectively a tax taken from employers and paid to employees in the form of health insurance. The many regulations that compel people and businesses to do things they might not otherwise do is an enormous cost, with some estimates of the cost exceeding 10% of the GDP.

What is the best way to tax?

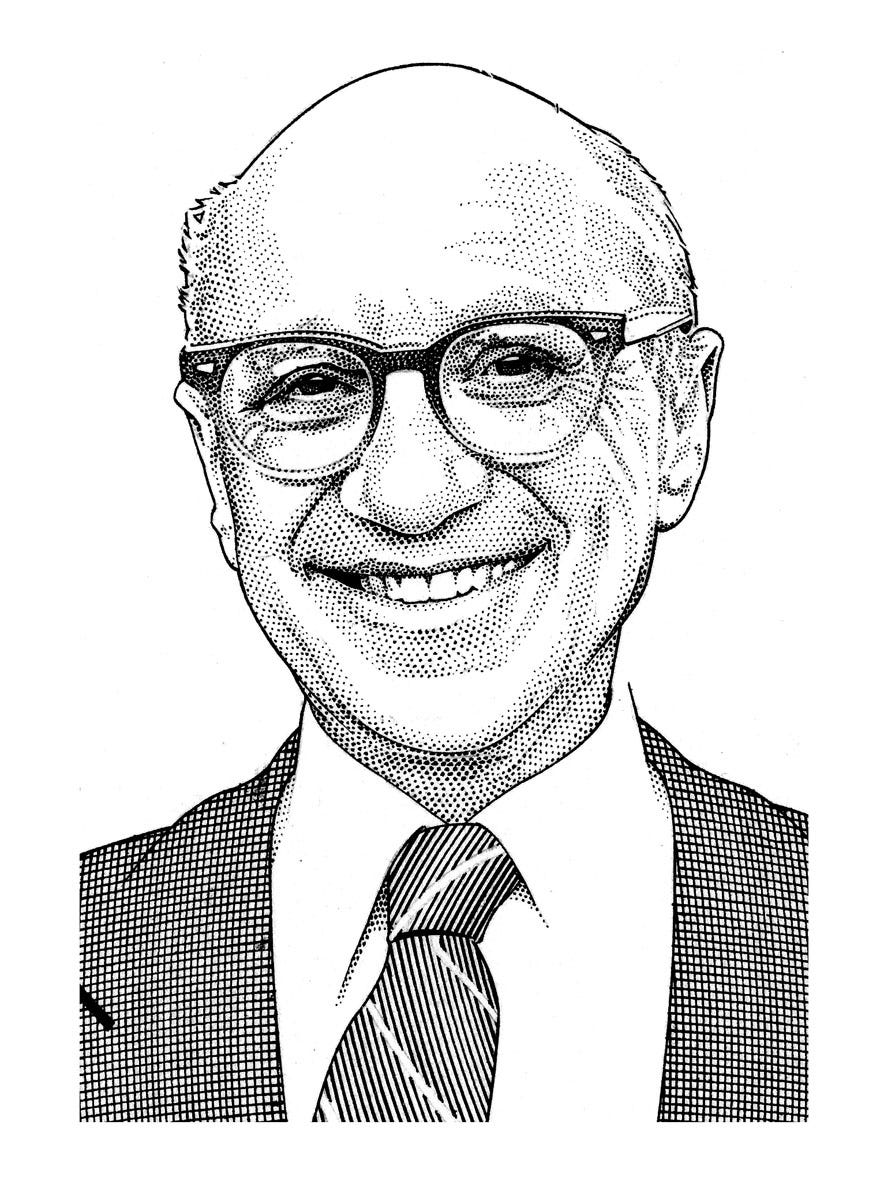

Option A: The Milton Friedman option

Milton Friedman opined that the “least bad tax” is the land value tax, and the “next least bad tax” is a flat rate tax on income above an exemption. I agree wholeheartedly with his opinion, with the qualification that select Pigouvian taxes can be pretty good as well if done right™.

The land value tax has many benefits that stem from the fact that its basically a Pigouvian tax that corrects substantial externalities. My next post will go into detail about the land value tax.

Part of the idea behind a flat tax on income above an exemption is that all the myriad of complications and loopholes would be eliminated. This of course assumes the political will to eliminate the tax labyrinth, which only exist precisely because they fulfill political purposes. The exemption would be desirable because it would be automatically progressive without the added complexity of tax brackets. Basically you’d do something like tax all income someone makes above $40,000. So if you make $50,000 in a year, you’d be taxed on the $10,000, and if you make $100,000 you’d be taxed on $60,000.

This option would involve eliminating basically all other taxes. Eliminate the sales and excise taxes, property tax, and tariffs. Roll capital gains, business taxes, and inheritance tax into income tax. All these cause distortions worse than income tax, and certainly worse than land value tax.

Option B: Only the most important changes

However, by far the most important thing to do is eliminate the tax labyrinth. The complexity of the tax code causes literally hundreds billions of dollars of losses in the US every year. So even without a massive shift to a different kind of tax, this could relieve a major headache and eliminate a lot of costs.

I also think business taxes should be shifted to individual business owners. It would reduce the perverse incentive for companies to merge and grow inefficiently large, and eliminating the sales tax would eliminate the perverse incentive entirely. And since business taxes have a flat rate, its essentially regressive, giving benefits for anyone in higher tax brackets but tax disadvantages to any stock holders in lower tax brackets.

And one more addition to this: it should be illegal to use fines to fund the government. Parking tickets, civil forfeiture, and the like should be given directly back to people. Allowing fines to fund government departments creates an extraordinarily perverse incentive for police to harass people and extract unjustly exorbitant fines and seizures for their own benefit.

Option C: Local taxes only

The nuclear option would be to only tax as the local level, and have states or nations take a percentage of taxes collected by each local jurisdiction. That way local jurisdictions can tax however they want to while still giving higher levels of government the funding they need. This could be even simpler for people, as they would only need to deal with one tax regime, rather than in the US where there are generally at least 3 or tax jurisdictions you might fall into.

Conclusion

Taxes are a big ole mess because of political incentives that serve special interests. The tax codes of countries are generally very far from what an economist might recommend. All taxes cause market distortions, and only a few of those can potentially be good distortions (these are the Pigouvian taxes). Next post I’ll go into the best one of these: Land Value Tax.